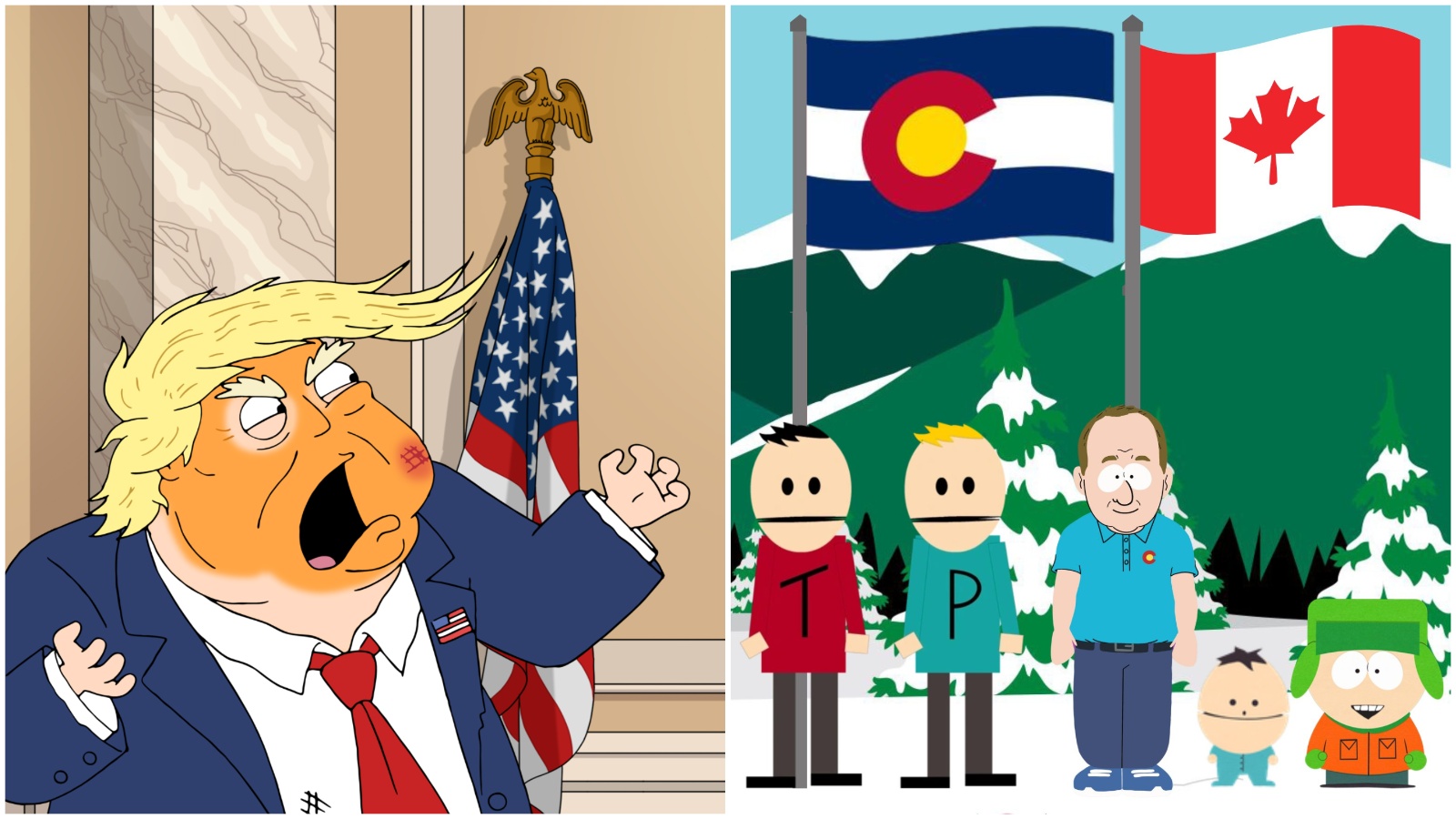

The Technate Of America: A Plan To Replace Partisan Politicians & Business People With Scientists & Engineers

This was basically a plan to run all of North America and some of South American by scientists and engineers rather than partisan politicians and business people.

Interestingly Joshua N. Haldeman, Elon Musk’s maternal grandfather, was a supporter of the plan between 1936 to 1941.

Here’s summary of Technocracy movement itself.

The Technocracy movement emerged primarily in the United States and Canada in the 1930s, advocating the replacement of representative democracy and traditional economic systems with governance by scientific and technical experts.

Its proponents argued that politics and economic decisions should be managed by engineers and scientists, believing this approach would result in a more rational, efficient, and productive society.

Technocrats believed that politics, partisan struggles, and monetary systems hindered rational social management.

Origins and Early Development

The term “technocracy,” coined in 1919 by engineer William H. Smyth, referred to governance through technical and scientific expertise rather than elected politicians or businesspeople.

Thorstein Veblen’s writings, particularly “The Engineers and the Price System,” significantly influenced the intellectual foundation of the movement.

Other early inspirations included Edward Bellamy’s utopian visions and the Progressive engineers of the early 20th century.

Early organizations such as Henry Gantt’s “The New Machine” and Veblen’s “Soviet of Technicians” experimented briefly with technocratic ideas but dissolved rapidly.

Formation and Prominent Figures

Howard Scott became the movement’s most notable figure, establishing the Technical Alliance in 1919 and later Technocracy Incorporated in 1933 after factional splits. Scott and his associates believed that only engineers and scientists could efficiently manage industrial economies.

The movement rapidly gained public attention during the Great Depression when traditional political systems struggled to address the economic crisis.

Core Ideology and Proposals

Technocrats asserted that traditional monetary economies (referred to as “price systems”) were inherently flawed because they created artificial scarcity.

Instead, they proposed “energy accounting,” a radical new economic model that used energy rather than currency as a measurement of value.

Citizens would receive Energy Certificates (later, Energy Distribution Cards), entitling them to an equal share of resources based on energy allotments rather than money. Certificates would expire, preventing hoarding, and ensure continuous, scientifically managed consumption.

The core vision was continental in scope, proposing a “Technate” spanning from Panama to the North Pole, exploiting abundant natural resources and geography to achieve self-sustainability.

Decline and Challenges

The movement’s popularity peaked briefly between 1932 and 1933 but quickly declined, partly due to skepticism about its feasibility and internal factionalism.

Howard Scott’s 1933 nationwide radio address was poorly received, damaging public perception.

Critics argued Technocracy Inc.’s ideas were overly elitist, dismissive of democracy, and politically naïve, especially as predictions of imminent economic collapse did not materialize.

During World War II, the movement faced temporary suppression in Canada, later cooperating with the war effort.

Post-war activity, however, dwindled significantly due to internal dissent, public skepticism, and the stabilization of traditional economic systems.

Key Elements of Technocracy’s Proposal

Technocracy Inc. proposed significant societal reforms:

- Energy Theory of Value:

Society would abandon monetary valuation, adopting energy as the fundamental economic measure. Economic transactions would be tracked through energy accounting, making monetary systems obsolete. - Abolition of Partisan Politics and Price System:

Elimination of traditional financial systems, bankers, politicians, and businesspeople, replacing them entirely with technical experts. - Scientific Social Engineering:

Society’s problems would be treated purely as engineering challenges, resolved by technical solutions rather than legislation. An example was redesigning streetcars without dangerous outer platforms instead of legislating passenger behavior. - Continuous, Efficient Work Scheduling:

Technocrats designed a four-day, four-hour-a-day workweek rotating among seven groups to ensure 24-hour productivity without interruptions, optimizing the use of resources, machinery, and infrastructure. - Energy-Based Continental Accounting System:

A detailed, continent-wide inventory system would track real-time energy conversion, availability, and usage, ensuring scientifically balanced resource distribution.

Organization and Aesthetics

Technocracy Inc. members wore distinctive gray uniforms with monad insignias symbolizing balanced production and consumption.

Gray became the official color, signifying uniformity and efficiency.

Publications often used industrial imagery and robots as visual metaphors, suggesting society managed by impartial, rational, technical control rather than human emotions or politics.

Influence and Legacy

Although the movement lost prominence after the mid-20th century, its influence persisted culturally.

Technocracy found representation in literature, games, and popular media:

- Literature: Technocratic ideas inspired works by Aldous Huxley (“Brave New World“), H.G. Wells (“The Shape of Things to Come“), and were indirectly referenced in science fiction by authors like Isaac Asimov.

- Video Games: Games such as “Stellaris,” “Victoria 3,” and “Hearts of Iron IV” (modifications) incorporated Technocratic governments, energy-based currencies, and organizational methods reflective of Technocracy Inc.’s original visions.

Comparison to Socialism

Technocracy, while sometimes conflated with socialism due to critiques of capitalism, fundamentally differed from socialist ideologies.

Socialists advocated worker democracy and egalitarian political participation. Technocracy, by contrast, rejected traditional politics entirely, entrusting societal control exclusively to technical experts, viewed as inherently elitist.

Howard Scott provocatively declared Technocracy to be even more radically egalitarian (“far left”) than communism, yet differed fundamentally by its outright rejection of political structures, whether democratic or revolutionary.

Legacy and Modern Status

Technocracy Inc. persisted into the 21st century, maintaining small-scale activities, newsletters, and websites (which you can still access here).

An archive of Technocracy’s historical materials is preserved at the University of Alberta, documenting its cultural and historical influence.

And here’s what Cornell Library says about the map itself:

This map illustrates “The American Technate,” a radical geopolitical proposal by a radical organization based on pseudo-scientific economics and authoritarian, nationalist politics.

As the Great Depression deepened in the early 1930s, Americans looked in desperation to a variety of radical social and political solutions. One of the most popular was “Technocracy,” which “offered a seemingly scientific explanation of America’s ills,” namely, the “disastrous inefficiency” of “the wage-price system, the very heart of capitalism.”

The technocrats proposed abandoning business and representative government as the driving forces of our economy, and replacing them with massive social engineering centered on “technicians – especially engineers . . . as the efficient, scientific, anticapitalistic, elite capable of reorienting the economic order around rational production and distribution. Theirs was a clarion call for technicians to plan and engineer the new order.” Akin 1977, ix-x.

“Politically unbiased experts in red-and-gray Technocracy uniforms would assay each nation’s yearly energy output, then divide it fairly among the citizenry.”

Goods and services could be purchased at prices set out “on a table of energy equivalents calculated by objective Technocratic savants,” all led by the “Great Engineer.” Mann 2018, 273. While originally based on energy calculations by scientists at Columbia University, the Technocracy dogma was written by “a charismatic Greenwich Village layabout named Howard Scott.”

Scott, who “dismissed the world’s businesspeople, social scientists, lawyers, and teachers as charlatans” (ibid., 273-74), was the long-time Director-in-Chief of Technocracy Incorporated. Its program was essentially a “techno-autocracy,” with a self-perpetuating elite, overt hostility to “aliens and Asiatics,” and a wide range of “fascist trappings.” Temple 1943, 118-119.

By the outset of World War II, the popularity of the Technocracy movement had declined substantially, but it continued to be active. In July 1940 – as war raged in Europe while America had not engaged – Scott published the organization’s position, “America – Now and Forever,” in the Official Magazine of Technocracy Inc. Consistent with the movement’s isolationist policy, it proposed a dramatic increase in the nation’s continental defense.

Among other things, the government was to greatly increase the size of the military; “conscript” all American means of transportation, communications systems, public utilities, manufacturing industries, mining enterprises, and patents; close all bars; “abolish” all foreign language periodicals, advertising, radio programs, and organizations; and prohibit outgoing transfers of currency (pp. 13-14).

Along with these proposed steps, Scott wrote that the territory of the United States must be expanded in order to defend it properly.

The new “Technate of America” was to include all of Canada, Greenland, Central America, the Caribbean, and parts of Columbia, Venezuela and the Guyanas.

“Defense Bases” were to be established around the perimeter as far afield as Attu; Pago Pago; the Galapagos; Georgetown, Guyana; Bermuda; St. John’s, Newfoundland; and Cape Farewell, Greenland.

In Scott’s words, “On the map accompanying this issue is delineated the geographical territory required for the adequate defense and operation of this Continental Area. . . . We should immediately acknowledge our planned intentions of consolidating these territories, not as separate political entities, but as part of the Continent of North America. . . . America must possess all North American territories on the accompanying map of the Technate, for the defense of this Continent.” (Pp. 10, 12.)

How to achieve this monumental consolidation?

“The government of the United States should take immediate action to acquire these territories and others, such as Greenland and the Galapagos Islands. The acquisition of these territories should be a mandatory part of the program of Continental defense for immediate achievement – either by purchase, negotiation, or the force of arms.” (P. 12.)

The success of the New Deal had already reduced the attractiveness of Technocracy’s economic and political proposals at the time this map was published, and the attack on Pearl Harbor ended support for the isolation of the United States.

What do you think about the plan?