Always Rooting For The Antihero: How Three Tv Shows Have Defined 21st-century America

“An outlaw can be defined as somebody who lives outside the law, beyond the law and not necessarily against it.”

–Hunter Thompson

*“All human advances occur in the outlaw area.”

–Buckminster Fuller

*

In the mid-1960s, network TV was suddenly awash in what scholars would later call “supernatural sitcoms.” My Favorite Martian featured an anthropologist from Mars who crash-lands in Los Angeles and hides out at a newspaper reporter’s apartment while he tries to repair his spacecraft. Mister Ed starred a talking horse who only speaks to his bumbling owner, Wilbur, and constantly gets him in trouble. Bewitched depicted a nose-twitching witch named Samantha who marries a nervous ad executive who insists she refrain from using her magical powers.

I Dream of Jeannie recounted the story of a genie named Jeannie who falls in love with an astronaut who finds her bottle when his space capsule splashes down near a deserted island. And The Addams Family concerned a macabre family with supernatural gifts who don’t understand why their neighbors think they are weird.

At the time, such shows were regarded as simple ditzy, escapist fun. Later, academics would argue that the sitcoms were products of the civil rights era of the day: They metaphorically examined the subjects of “mixed marriages” and integration; and in the case of Bewitched and I Dream of Jeannie they reflected growing tensions between empowered women and men who want them to just be ordinary, stay-at-home housewives.

In retrospect, those comedies can also be seen as portraits of outsiders trying to negotiate a path, in mid-twentieth-century America, between identity and assimilation, and the shifting attitudes of family, neighbors, and co-workers toward them. There are some cringe-inducing moments—Jeannie, in particular, can sound like a desperate-to-please geisha—but for the most part it’s the outsiders who come across as insightful and charming, possessed of both common sense and a resilient sense of humor, while their human counterparts emerge as uptight, dim-witted dolts, morally superior and comically self-deluded.

In these shows, America is already a place where more and more people’s dreams are running aground.For that matter, Americans have long had a fascination with outsiders. Though none were dangerous norm-busting conmen like Donald Trump, many U.S. presidents in recent decades ran as Washington outsiders—including Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama. And when it comes to entertainment, Americans have demonstrated an enduring love-hate affair with outlaws, renegades, and rebels with (and without) a cause. Think: James Dean, Marlon Brando, Humphrey Bogart, Montgomery Clift. Think: Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Midnight Cowboy, Cool Hand Luke, Easy Rider, Edward Scissorhands, and, well, The Outsiders. Many classics from the great movie decade of the 1970s feature misfits, killers, and mavericks including Five Easy Pieces (1970), Klute (1971), The Godfather (1972), Badlands (1973), Serpico (1973), Mean Streets (1973), Dog Day Afternoon (1975), One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Carrie (1976), and Taxi Driver (1976).

And it’s not just crazed killers like Travis Bickle, Tony Montana, and Marvel villains (and for that matter, some Marvel heroes) who live beyond the bounds of the law, but also cops like Harold Francis Callahan (a.k.a. Dirty Harry) and Max Rockatansky (a.k.a. Mad Max). The premise of many detective and private eye stories is that their unconventional hero or heroine is more adept, more observant than the bureaucrats in the police department: This dates back to PIs like Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe in hard-boiled classics, through generations of TV detectives from Columbo and Jim Rockford, to Jessica Fletcher (Murder, She Wrote) and Charlie ’s Angels and, more recently, Adrian Monk.

As we entered the new millennium, three daring TV series remade the television landscape, and they all featured a new breed of outsider: lawless, desperate, violent characters once unimaginable on the small screens in our living rooms. These antiheroes inhabit an America that’s lost its way—a broken world where institutions are corrupt, incompetent, or both—and people feel angry, trapped, and discouraged.

Indeed, the country depicted in The Sopranos (1999–2007), The Wire (2002–08), and Breaking Bad (2008–13) is recognizably the country that would elect Donald Trump a few years later—a place where, as David Chase’s mob boss Tony Soprano says, “things are trending downward,” where, in the words of a character in David Simon’s The Wire, “we used to make shit in this country. Build shit. Now we just put our hand in the next guy’s pocket.”

In these shows, America is already a place where more and more people’s dreams are running aground, where the poor and the middle class find it increasingly difficult to make ends meet, and where even the privileged feel a sense of emptiness and disappointment. No doubt this is one of the reasons viewership of The Sopranos on HBO’s streaming service surged 179 percent during the pandemic. The series spun off several popular podcasts, and thirteen years after ending its original run was hailed by GQ as “the hottest show of 2020.”

The legions of new Gen Z fans acquired by David Chase’s groundbreaking series no doubt understood Tony Soprano’s explanation for why he was feeling depressed. “It’s good to be in something from the ground floor,” the mob boss told his therapist, Dr. Melfi, in the show’s pilot. “I came too late for that, I know. But lately, I’m getting the feeling that I came in at the end. The best is over.” Thinking about his father, Tony adds, “He never reached the heights like me, but in a lot of ways he had it better. He had his people, they had their standards, they had their pride. Today, what do we got?”

As for Tony’s wayward son A.J., he becomes preoccupied with Yeats’s vision of things falling apart in “The Second Coming” and sums up his feelings about America this way: “This is still where people come to make it, it’s a beautiful idea.” But “what do they get? Bling? Come-on’s for shit they don’t need and can’t afford?”

Worries that the United States had entered a downward spiral aren’t new, of course. But for much of its history, America has been relentlessly forward-looking—convinced, like the early settlers who had left behind the Old World, that America was a New World where they could reinvent themselves, where, as Tocqueville observed, “everything is in constant motion, and every movement seems an improvement.”

But in recent years, the belief, as Scarlett O’Hara put it, that “tomorrow is another day” has dwindled, with studies showing that millennials—facing uncertain career prospects, saddled with college debt, and priced out of a rising housing market—are on track to be the first generation in the nation’s history that will fail to exceed their parents in income or job status.

And then there is Donald Trump: Whereas earlier presidents routinely invoked the future (whether it was the New Deal or building an interstate highway system or embarking on the race to space), Trump ran on a promise to “Make America Great Again”—which was really code for turning the clock back to the pre-civil-rights days, when white men made the rules and African Americans, women, Latinos, LGBTQ+ people, and immigrants were consigned to the margins.

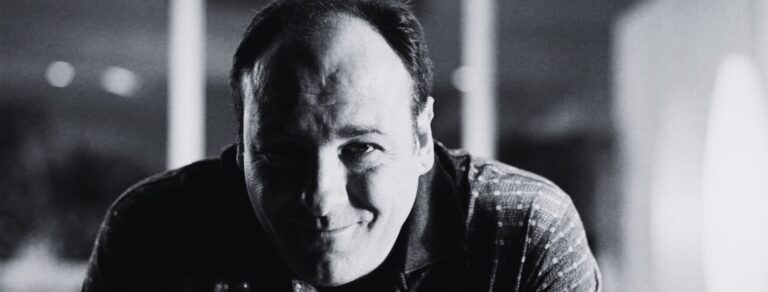

Because the great James Gandolfini invested his portrayal of Tony with such nuance and swaggering charm, because he made Tony’s frustrations with daily life so recognizable and real, audiences tended to identify with the mob boss—never mind that he killed eight people and presided over a ruthless gang of crooks and hit men. In his 2013 book, Difficult Men, Brett Martin argued that “no genre suited the baby boomers’ dueling impulses of attraction and guilt toward American capitalism as well as the Mob drama.

The notion that the American dream might at its core be a criminal enterprise lay at the center of the era’s signature works, from Bonnie and Clyde and Chinatown to The Godfather and Mean Streets”—and The Sopranos “yoked that story to one of postwar literature’s most potent tropes: horror of the suburbs,” which had come, in much postwar literature, “to represent everything crushing and confining to man’s essential nature.”

Breaking Bad, too, was a dark parable about American decline. Viewers started out feeling they could relate to Walter White, the high school science teacher who found himself diagnosed with cancer, unable to afford medical treatments, and worried about supporting his family. And some viewers continued to root for Walt, even as he metamorphosed, in the words of the show’s creator, Vince Gilligan, “from Mr. Chips into Scarface.”

Initially, Walt’s decision to use his knowledge of chemistry to start cooking meth is spurred by financial desperation: Given eighteen months to live, Walt wants to leave his pregnant wife and their disabled son a nest egg for when he is gone. Figuring out the cost of college for two kids, mortgage payments on the house, and the daily costs of living (adjusted for inflation), he calculates that he needs to make $737,000—an amount impossibly beyond his teacher’s salary, even when supplemented with pay from his second job at a local car wash.

And so, in a kind of dark twist on the American myth of the self-made man, Walt becomes a successful entrepreneur—a master meth cook and drug kingpin who goes by the name of Heisenberg. “I am not in danger, Skyler,” he tells his worried wife. “I am the danger. A guy opens his door and gets shot, and you think that’s me? No! I am the one who knocks!”

The notion that the American dream might at its core be a criminal enterprise lay at the center of the era’s signature works.The critic Alan Sepinwall (The Revolution Was Televised) makes the keen observation that The Sopranos and The Wire are both “shows about the end of the American dream,” but whereas the first “comes across as deeply cynical about humanity,” the latter “believes that any innate goodness within people eventually gets ground down by the institutions that they serve.” “The America of The Wire is broken,” Sepinwall goes on, “in a fundamental, probably irreparable way. It is an interconnected network of ossified institutions,” all of them “committed to perpetuating their own business-as-usual approach” and preserving the status quo regardless of the human costs.

A choral portrait of the city of Baltimore, The Wire introduces dozens of characters—cops and drug dealers, reporters, politicians, dockworkers, schoolkids, lawyers, gang members, businessmen, police informants, and junkies—and shows us how “all the pieces matter,” how decisions made by those with power or influence can have devastating fallout on the lives of those who have neither, those men and women who, in the words of the show’s creator, David Simon, were “left in the shallows” by the American economy: “unemployed and underemployed, idle at a West Baltimore soup kitchen or dead-ended at some strip-mall cash register.”

And those folks who aren’t jobless tend to work for organizations—whether the police department or a drug empire—that grind them down or get them killed. Not surprisingly, the series’ most captivating character is a quintessential outsider—Omar Little, played by the brilliant Michael K. Williams, a gay stickup man who works for no one and adheres to his own strict code of honor, a feared and fearless badass who can also be generous, tender, and loyal.

The Wire and The Sopranos changed television storytelling, made TV the hot, go-to medium, and opened the way to a host of new antiheroes, each darker than the next. In addition to Walter White, there was the crooked cop Vic Mackey (The Shield), the Machiavellian congressman Frank Underwood (House of Cards), the gangster/politician Nucky Thompson (Boardwalk Empire), the ruthless lawyer Patty Hewes (Damages), the serial killer Dexter Morgan (Dexter), the duplicitous Don Draper (Mad Men), the scheming Cersei Lannister (Game of Thrones), the money launderer Marty Byrde (Ozark), the drug lord Teresa Mendoza (Queen of the South), and the toxic media mogul Logan Roy in the iconic series of the Trump era, Succession.

In The Sopranos Sessions, Steven Van Zandt, who played Tony’s consigliere Silvio Dante, told the book’s authors, Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall, that audiences often focus on “the romantic version of the criminal lifestyle” where the gangster is “the guy who breaks all the rules and gets away with it, at least for a while”; “it’s booze and broads and horses and dice and killing a guy if he gets in your way and not caring what anybody thinks of you.”

It wasn’t just the case with Mafia movies and TV shows, Van Zandt added: “It’s Cagney and Bogart movies, it’s Westerns. America seems to have some kind of fascination with outlaws in general. Maybe it’s because we were an outlaw nation to begin with. This nation was born of rebellion against authority, and in a weird way, that’s what these characters represent. That image is very attractive to Americans. It’s part of the national unconscious. It’s practically in our genetic code.”

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Great Wave: The Era of Radical Disruption and The Rise of The Outsider by Michiko Kakutani. Copyright © 2024 by Michiko Kakutani. Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.