These Ai-powered Textiles Are Designed Specifically For People With Dementia

Anyone who visits Wong Tai Sin, a healthcare center in the northern part of Hong Kong, will be welcomed by a curious sight. At first glance, the three illuminated panels hanging on the wall appear to be artworks depicting local landmarks like the Kai Tak River, or Morse Park. But if you give one of the panels a thumbs-up, the panels switch from blue to green. If you raise your arms above your head, the lights flick to yellow.

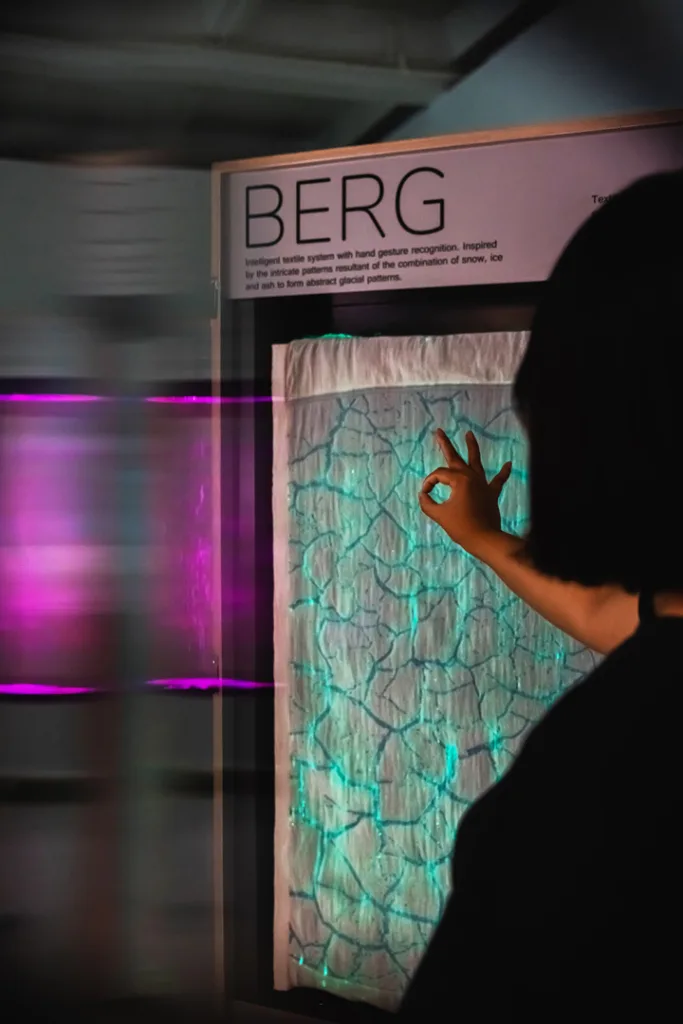

The panels—made from illuminated textiles comprised of polymeric optical fibers stretched taught around a frame—are more than eye candy: They are interactive tools designed to stimulate the senses and encourage dexterity and mobility in elderly patients. Each panel has a tiny integrated camera that is linked to an AI-powered computer vision model trained to recognize particular hand or body gestures, then light up in response.

[Photo: courtesy AiDLab]These “intelligent textiles” were designed by Jeanne Tan, an associate professor at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University, in collaboration with occupational therapists. Since they were first installed in 2021, they have been so popular that they inspired the team to design a knitted pillow that can change colors when you press or stroke various parts of it, an interactive screen divider for people with advanced dementia, and a smaller, more portable interactive box with a textile screen inside it. The team can program each of these textiles to respond to various gestures, even when the gestures aren’t 100% perfect.

“I wanted to encourage [therapists] to use them for sensory therapy and as a means to gamify and encourage simple exercises,” Tan says.

[Photo: courtesy AiDLab]Designing for dementia

People with dementia can have problems with many aspects of daily life, including thinking, memory, behavior, and mobility. In many cases, if their senses are not stimulated, and they have nothing to do, they might become frustrated, agitated, and deeply distressed. This is particularly true for people with advanced dementia, who may have lost their cognitive abilities and require simpler activities that stimulate their senses.

“A puzzle won’t do, so you need to find things they can do on their level but still find joy and some sort of satisfaction and sense of purpose,” says Anke Jacob, a design researcher at Kingston University in the U.K., who wasn’t involved in the intelligent textiles project but whose research focuses on sensory design for dementia care environments.

A therapy known as multisensory stimulation is becoming increasingly popular among therapists and carers who need to manage the behavioral and psychological symptoms that accompany dementia. Textiles are uniquely positioned to help people with dementia because they are tactile, flexible, and, in the case of intelligent textiles, interactive. “The combination of lights and textiles has potential,” says Jacob, who’s also a textile designer by background. Unlike “cold, plasticky buttons” that could put people off, she says, textiles are more accessible.

[Photo: courtesy Jeanne Tan]AI-powered textiles

Back in Hong Kong, Tan has been working in the field of e-textiles for more than a decade. Most recently, her color-changing garments were on display during Milan Fashion Week in 2023. But since the beginning of the pandemic, Tan and her team have also been researching how interactive textiles can be used in rehabilitation, specifically for people with dementia.

Tan first came up with the idea over dim sum (“as with all things in Hong Kong,” she tells me with a laugh), after learning that people with advanced dementia tend to fidget, and even explore objects through their mouths. Maybe we should try and find something they can interact with, she thought to herself. “Those who like tactility can touch, those [who don’t] can use gesture recognition,” she says.

From the very beginning, Tan knew she wanted the textiles to be knitted. Unlike cut and sewn fabric, knitwear doesn’t produce any waste material. Together with her team, she also developed a special kind of polymeric optical fiber that can emit light throughout the fibers (as opposed to just at the tip), so the entire textile can light up homogeneously.

It took the team two years to figure out how to knit the fabric using standard industrial machines so the textile production could be scalable. It took another year to fine-tune the computer model so it can respond to hand gestures with various degrees of leniency. “We wanted to transform a mundane piece of fabric into something that people of all abilities can use,” Tan says.

[Photo: courtesy Jeanne Tan]A market with potential

According to the World Health Organization, more than 55 million people around the world have dementia, and that number is expected to reach 139 million by 2050. And yet, just 10 years ago, Jacob from Kingston University says there was academic research about the benefits of multisensory stimulation for people with dementia, but little to no research about what these multisensory stimulation tools should look and feel like.

In the past, she says, patients were likely given children’s toys to occupy themselves. In 2013, Jacob published what may have been the first guidebook developed to help staff in care homes design sensory rooms for people with dementia. The market is growing, but that’s not to say it is saturated. “We are not there yet,” she says.

Today, people living with dementia—and those caring for them—have an increasing number of therapeutic objects to choose from, including Hug, a soft doll that can simulate a heartbeat, play a favorite playlist, and wrap its arms and legs around someone’s body; and a plush “dementia fidget toy” reminiscent of a chatterbox. There are also twiddle muffs, activity pillows, and even a therapeutic robot that looks like a soft seal (made, naturally, in Japan).

Meanwhile, Tan’s intelligent textiles and touch-reactive pillows have been used in a healthcare center, an elderly care center, and an assisted living company called Ventria. In an admittedly small study among 20 participants, the team found that patients were almost twice as likely to engage with touch-reactive pillows than the vibrating pillows typically used in dementia care.

Tan hopes to continue scaling up the textiles through a spin-off company she recently founded, called Geri. Beyond healthcare environments, she says people have also expressed interest in buying these products for their loved ones at home. “The aging population is a serious problem,” she says. “We hope that more people reach out to us so our work can reach more people.”