Have State Auto-iras And Fintech Shifted Who Contributes To Iras?

The brief’s key findings are:

- IRAs were created to help those without an employer plan to save, but most IRA assets are simply rollovers from 401(k)s, not new contributions.

- Recently, though, the share of households contributing to an IRA has ticked up – a little bit for low-income workers and a lot for those under 40.

- The rise in low-income contributors could well be due to state auto-IRA initiatives, which have broadened access to workplace-based plans.

- The surge in younger contributors is most likely due to new fintech platforms that promote IRAs to tech-savvy Millennials.

- But these younger contributors tend to have a 401(k) too, so IRAs remain mainly a way for those with a plan to gain more tax-advantaged saving.

Introduction

Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), which hold over half of total private retirement assets, were introduced as a way for workers without an employer-sponsored plan to save for retirement in a tax-advantaged account. Instead, they have been primarily used as a vehicle for rollovers from employer-sponsored plans, with direct contributions traditionally accounting for only a small share of annual inflows.

In recent years, however, two developments could have affected contributions: 1) the spread of state auto-IRA programs, which enroll workers without coverage into a Roth IRA; and 2) the growth of fintech platforms offering, and sometimes incentivizing, IRA contributions. If IRA contributions have increased and that increase is driven by auto-IRA programs, it would mean that IRAs are now fulfilling their original intent of providing retirement savings for the uncovered. If the increase is driven by fintech platforms, popular among the young, higher-income, and tech-savvy, it would mean that IRAs are still mainly a vehicle for those who already have savings to gain more tax advantages. This is a good time to reassess the pattern of contributions to IRAs.

The discussion proceeds as follows. The first section provides a brief history of IRAs. The second section describes the inflows into IRAs, documents the recent increase in the share of households contributing, and describes the two developments – state auto-IRA programs and fintech platforms – that may be driving the recent increase in IRA contributions. The third section assesses the importance of these initiatives by exploring changes in the characteristics of IRA contributors.

The results suggest that auto-IRAs, where total accounts are only about one million, may have contributed to the small uptick in contributions among the households in the lowest third of the income distribution. The main action, though, seems to have been spurred by fintech, which appears to have sharply increased contributions among younger households in the top third of the income distribution who already have a 401(k)-type plan. Thus, IRAs remain primarily another tax-advantaged saving option for those with existing retirement assets rather than a mechanism for increasing coverage.

A Brief History of IRAs

Traditional IRAs were introduced in 1974 under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). The goal was to enable those without employer-sponsored retirement plans to save in a tax-deferred fashion. That is, the government does not tax the original contribution to an IRA nor the returns on those contributions until the funds are withdrawn from the plan. Withdrawals from traditional IRAs before age 59½ are generally subject to a 10-percent penalty and people must begin to withdraw their funds by age 73 in accordance with the current required minimum distribution (RMD) rules.

Although eligibility was initially limited to those without pensions, it was expanded in 1981 to encompass all workers. It soon became evident, however, that while IRAs were offered to all, they were being used primarily by higher-income people. As a result, Congress substantially tightened IRA provisions in the Tax Reform Act of 1986. These changes made contributions to IRAs fully tax deferred only for people who were not active participants in an employer-sponsored plan or whose adjusted gross income (AGI) fell below certain thresholds.1

The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 made more changes, including the creation of the Roth IRA.2 In contrast to the traditional IRA, initial contributions to Roth IRAs are not tax deductible, but investment earnings accrue tax free and no tax is paid when the money is withdrawn. In addition, holders of Roth IRAs do not face any RMD. While traditional and Roth IRAs may sound quite different, in fact they offer virtually identical tax benefits over any given time period.3

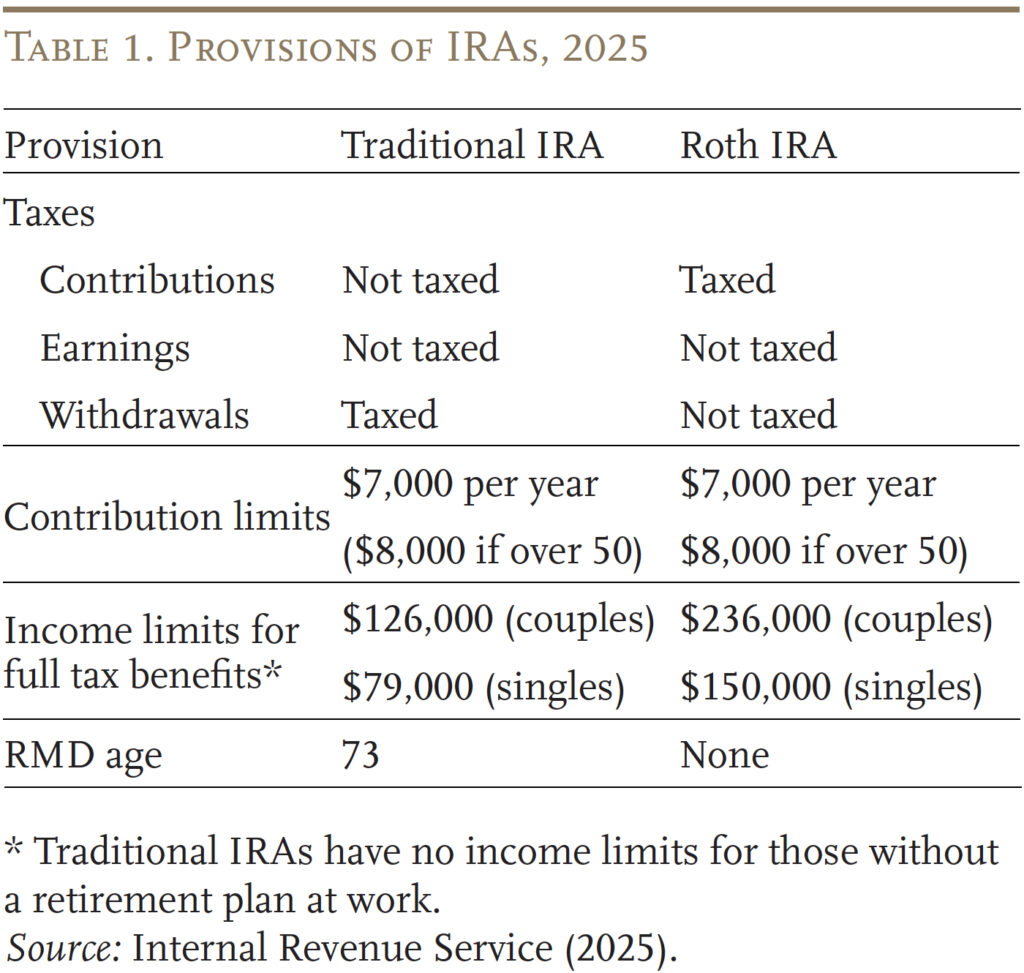

In 2001, both traditional and Roth IRAs allowed a maximum contribution of $2,000. The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 raised these limits gradually to $5,000 and indexed them for inflation annually in $500 increments. The legislation also permitted individuals ages 50 and over to make “catch up” contributions.4 As a result, contribution limits in 2025 are $7,000 for most and $8,000 for those over 50. Table 1 summarizes the current provisions for traditional and Roth IRAs.

In 2023, according to the Investment Company Institute, 55.5 million households – 42 percent of total households – owned an IRA (see Table 2). Households with traditional IRAs continue to outnumber those with Roths. Note that the percentages with the various types of IRA do not add to “any IRA” because many households have more than one type of account.

Today, assets in IRAs account for over half of all assets in private sector retirement plans, far exceeding those in either defined benefit or defined contribution plans (see Figure 1).

Inflows to IRAs

Most of the new money flowing into IRAs each year is rolled over from employer-sponsored retirement plans rather than coming from individual contributions (see Figure 2). The major reason for rollovers is that workers do not want to leave their money with their old employer, but often face difficult and time-consuming hurdles when trying to move money to their new employer’s 401(k). Since they want to preserve the tax-favored treatment of their savings, most workers roll over to an IRA. Workers also like the idea of consolidating a number of retirement accounts in a single location or gaining access to more investment options.

Despite the importance of rollovers, in 2023, about a third of households that owned a traditional or Roth IRA – 15 percent of total households – contributed to their account in the previous tax year. As shown in Figure 3, this share has ticked up in recent years.

Two potential developments could be behind the recent growth in IRA contributions: 1) the increase in the number of states launching auto-IRA programs for uncovered workers; and 2) fintech companies offering enticing bonuses for opening a new IRA.

State Auto-IRA Programs

State auto-IRA programs have gained steam over the past five years. These programs mandate that employers that do not offer their own retirement plan must automatically enroll their workers in an IRA. Currently, 11 states have launched mandatory programs.5 Between 2019 and 2024, the number of funded accounts in these state auto-IRA programs grew from 50,000 to 965,000 (see Figure 4). IRAs are fulfilling their original purpose for participants of state programs, allowing workers without a workplace plan to save rather than serving merely as a rollover vehicle. Many of the participants are low- and moderate-income workers, so auto-IRA programs had only reached $1.8 billion in assets by the end of 2024.6

Fintech Companies

Fintech companies have grown in popularity in recent years, particularly among younger investors. Originally, these firms focused on individual brokerage accounts, drawing in investors by cutting down the costs and complexities of investing. Since the pandemic, many have begun to offer enticing bonuses for transferring or contributing assets to an IRA.7 Robinhood, for example, announced it would be offering IRAs in December 2022. By December of 2024, just two years later, it had about 1.2 million accounts with over $13.1 billion in assets.8 Of course, much of the money in the accounts is likely rollovers, but some could also be new contributions. Indeed, fintech companies have suggested that their platforms can help gig workers save for retirement.9

The question is whether the state auto-IRA and fintech initiatives have altered the composition of contributors.

Characteristics of IRA Contributors Today

To answer this question, the analysis shifts to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances. Table 3 shows the characteristics of IRA contributing households for 2016, 2019, and 2022. At first, the pattern looks much the same across the years. Contributors to IRAs tend to be a fairly privileged group. About two-thirds of these households are in the top third of the income distribution, and they are mostly White, married, and college educated. Two changes, however, stand out. First, the share of contributors in the bottom third of the income distribution rose from 5 percent to 9 percent and, second, the share of contributors under age 40 increased from 28 percent to 41 percent. Are these changes related to the auto-IRA and fintech initiatives?

One piece of evidence that auto-IRAs and fintech might have facilitated the growth of IRA contributions is that “Roth only” contributors now account for a majority of total contributors (see Table 4). Lower-earning uncovered workers and young workers tend to benefit more from Roth accounts.

But how much of an impact could each initiative have had? The impact of the new auto-IRA programs must by definition be modest, since the total number of contributors is only about one million – compared to 20 million IRA contributing households in 2022. Yet, these programs could well explain the increase between 2019 and 2022 in the share of contributions coming from the bottom third of the income distribution – households in 2022 with incomes under $52,000. These are likely new savers who are gaining access to tax-advantaged options through Roth IRAs.

Similarly, fintech must surely explain the shift in the age distribution of contributors – generally, only young tech-savvy investors turn to their cell phones to save for retirement. But who are these new young IRA contributors? As shown in Table 5, the increase in the percentage of under-40 households contributing is concentrated among the top income tercile – the third of households with the highest incomes. The middle tercile also shows a modest increase – albeit from really low levels.

The question remains whether the fintech-inspired growth in contributions has produced an increase in coverage or just allowed households that are already covered easy access to another account. Table 6 shows that for the top tercile – the place with all the action – 82 percent of contributors already had a 401(k)-type plan. The bottom line seems to be that if technology makes it really easy to contribute to tax-advantaged savings accounts, the tech-savvy with money will take advantage of the opportunity.

Conclusion

IRAs were introduced to help workers without an employer-sponsored plan to save for retirement in a tax-advantaged account. Instead, they have been primarily used as a vehicle for rollovers from employer-sponsored retirement plans, with direct contributions – traditionally from high-income households – accounting for only a small share of annual inflows.

In recent years, the spread of state auto-IRA programs and the growth of fintech platforms could have increased contributions, changed the composition of contributors, and perhaps improved the share of workers with access to tax-advantaged saving. Indeed, the percentage of households contributing to IRAs did increase between 2019 and 2022. Auto-IRAs, where total accounts are only about one million, may have contributed to the small uptick in contributions among the households in the lowest third of the income distribution. The main action, however, seems to have been spurred by fintech, which appears to have sharply increased contributions among younger households in the top third of the income distribution. Most of these households, however, already have a 401(k)-type plan. Thus, IRAs remain primarily a way for those with retirement assets to gain more tax-advantaged saving rather than a mechanism for increasing the share of workers with access to work-based savings plans.

References

California State Treasurer. 2024. “Participation Reports.” Sacramento, CA: CalSavers Retirement Savings Board.

Center for Retirement Initiatives. 2025. “State Program Performance Data.” Washington, DC: Georgetown University, McCourt School of Public Policy.

Colorado Department of the Treasury. 2024. “Colorado SecureSavings Annual Report April 2024.” Denver: CO.

Connecticut Office of the State Comptroller. 2024. “Retirement Security Program Monthly Data Reports.” Hartford, CT.

Illinois State Treasurer. 2024. “Secure Choice Performance Dashboards.” Springfield, IL: Illinois Secure Choice.

Internal Revenue Service. 2025. “Retirement Plan and IRA Required Minimum Distributions FAQs.” Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Investment Company Institute. 2024. “The US Retirement Market, First Quarter 2024.” Washington, DC.

Investment Company Institute. 2017, 2020, and 2023. “The Role of IRAs in U.S. Households’ Saving for Retirement.” ICI Research Perspective. Washington, DC.

Maryland Small Business Retirement Savings Board. 2024. “MarylandSaves Monthly Dashboard Reports.” Baltimore, MD.

Munnell, Alicia H. and Anqi Chen. 2016. “Could the Saver’s Credit Enhance State Coverage Initiatives?” Issue in Brief 16-7. Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for Retirement Research at Boston College.

Oregon State Treasury. 2024. “Monthly OregonSaves Program Data Reports.” Salem, OR: Oregon Retirement Savings Board.

Robinhood Markets, Inc. 2025. “Earnings Presentation, Fourth Quarter 2024.” (February 12). Menlo Park, CA.

Topoleski, John J. 2008. “Traditional and Roth Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs): A Primer.” CRS Report 7-5700. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Financial Accounts of the United States: Flow of Funds Accounts, 2024. Washington, DC.

U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Survey of Consumer Finances, 2016, 2019, and 2022. Washington, DC.

Virginia Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission. 2024. “Virginia529 Oversight Report 2024.” Richmond, VA.

Endnotes

- The AGI thresholds at the time were $40,000 for couples and $25,000 for individuals. ︎

- The 1997 legislation also gradually increased the income thresholds for fully deductible IRAs and introduced a spousal IRA.

︎

︎ - Note that the Roth IRA is more generous in terms of contribution amounts. This difference is not obvious given as described below that individuals could contribute $7,000 under either plan in 2025. But for the individual in the 25-percent personal income tax bracket, a $7,000 after-tax contribution is equivalent to $8,750 before tax.

︎

︎ - The legislation also created the Saver’s Credit, a non-refundable tax credit that is in addition to a tax deduction, for households under certain income limits. For a discussion of the Saver’s Credit, see Munnell and Chen (2016). For more general information on the legislation, see Topoleski (2008).

︎

︎ - These programs are now up and running in California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont, and Virginia, with another five states preparing to launch.

︎

︎ - Center for Retirement Initiatives (2025).

︎

︎ - Fintech firms like Sofi, Robinhood, and Webull all offer bonuses for transferring money into an IRA.

︎

︎ - These data are from Robinhood Markets, Inc. (2025).

︎

︎ - However, many of these programs have only just launched, such as a retirement plan for independent workers started by Robinhood, which is partnering with companies such as Grubhub, Task Rabbit, and GoPuff. It is too early to tell if the platforms will actually help gig workers save for retirement.

︎

︎