On Najwan Darwish

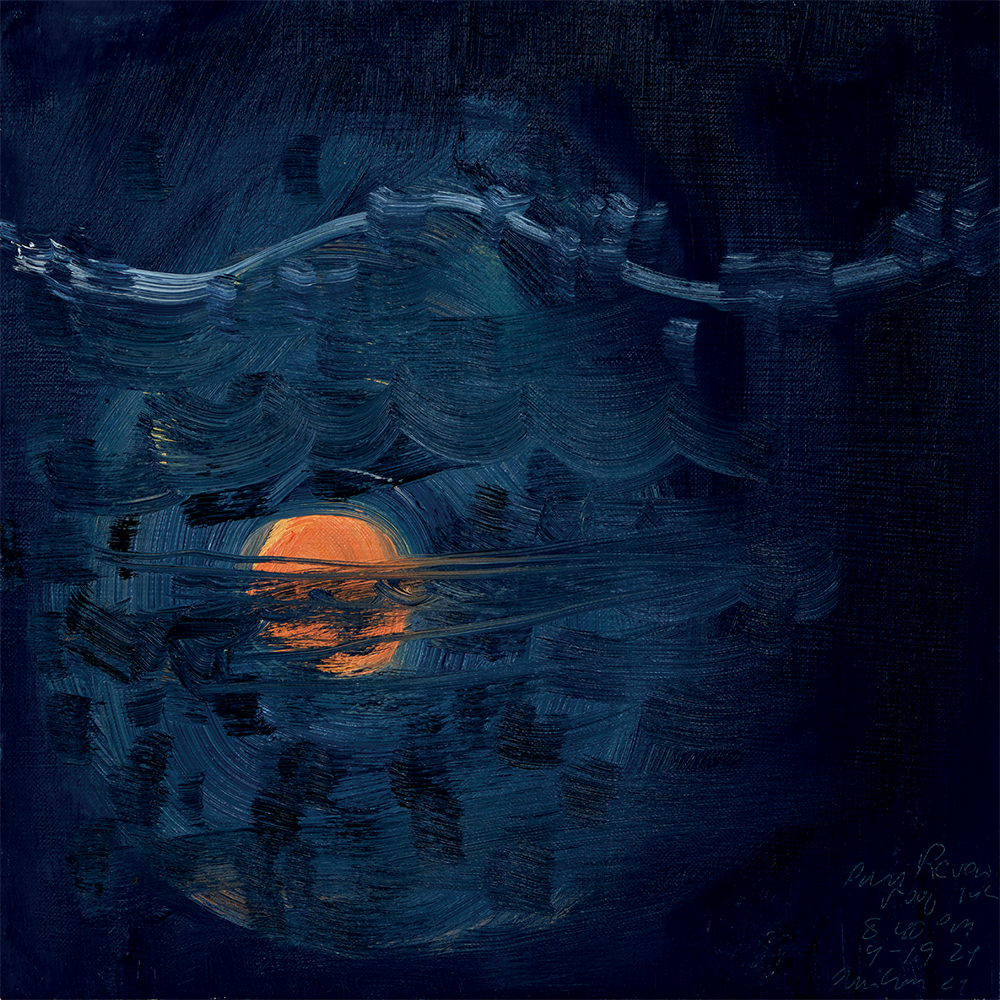

Ann Craven, Moon (Paris Review Roof, NYC, 9-19-24, 8:40 PM), 2024, 2024, oil on linen, 14 x 14″.

“No one will know you tomorrow. / The shelling ended / only to start again within you,” writes the poet Najwan Darwish in his new collection. Darwish, who was born in Jerusalem in 1978, is one of the most striking poets working in Arabic today. The intimate, carefully wrought poems in his new book, , No One Will Know You Tomorrow, translated into English by Kareem James Abu-Zeid, were written over the past decade. They depict life under Israeli occupation—periods of claustrophobic sameness, wartime isolation, waiting. “How do we spend our lives in the colony? / Cement blocks and thirsty crows / are the only things I see,” he writes. His verses distill loss into a few terse lines. In a poem titled “A Brief Commentary on ‘Literary Success,’ ” he writes, “These ashes that were once my body, / that were once my country— / are they supposed to find joy / in all of this?” Many poems recall love letters: to Mount Carmel, to the city of Haifa. To a lover who, abandoned, “shares my destiny.” He speaks of “joy’s solitary confinement” because “exile has taken / everyone I love.” Irony and humor are present (“I’ll be late to Hell. / I know Charon will ask for a permit / to board his boat. / Even there / I’ll need a Schengen visa”), but it is Darwish’s ability to convey both tremulous wonder and tragedy that make this collection so distinct.

Darwish has talked about the concept of poet as historian in interviews (“we drag histories behind us,” he has written) and No One Will Know You Tomorrow contends with the grief of the Palestinian people since the Nakba of 1948 and amid the genocide currently taking place. But it would be a mistake to reduce Darwish to a “wartime” poet. As Abu-Zeid points out in his introduction to the book, Darwish is doing something more complex: writing across time and place, geography and religion; drawing on a deep well of artistic heritage to inform the present. (“My country is an Andalus of poems and water, / I lost it, / I’m still losing it— / in loss / it becomes my country.”) Darwish also brings the history of Palestinians in relation to those of other peoples in diaspora. For Armenians, Kurds, Baha’i, Syrians, and others, “the earth—all of it—is a house of refuge. / The people—all of them—are citizens of dust.” Literary figures, living and dead, haunt these pages, from legendary pre-Islamic poets like Antarah and Sufi mystics to the Egyptian poet Hafez Ibrahim and the Syrian poet Adonis. “I have so many friends / sleeping in tombs from different ages— / at night I tell them stories, / more often than I should,” he writes in a poem dedicated to Yahya Hassan, the Danish Palestinian poet who died in 2020. “Come tell me stories and stay / above the ground. I’ve company enough already / beneath it.”

Darwish rarely gives interviews, but I spoke with him for the Guardian at the end of 2023. He was grappling with the horror of Israel’s war on Gaza, which has left more than forty-six thousand Palestinians dead and injured and displaced many more. It has taken his friends and fellow artists; wiped out entire families so there’s no one to call to express condolences, he said. Images of Gazan children haunt him. He spoke to me about filling a notebook with poems after October 7 and losing it at an airport; he thought he might never write again. Notebooks appear in several poems in No One Will Know You Tomorrow (“the last page in a notebook, / the last lip, / the last finger, / the last thread of light, / the last bit of darkness”), and I came to see them as a sort of talisman against forgetting: a way to record the dignity of Palestinians, and a bulwark against the colonizers that rewrite history to their advantage.

The last poem in the collection, “Endless,” could be read as an elegy, or a ringing call to action—even if that action is to, against all odds, survive. “In utter darkness, / in light, / in ruin, / in psalms, / in a trumpet, / in the horn of Israfil, / in a labyrinth,” he writes, “in an end that leads / to an endless end, / I lived.”

Alexia Underwood is a writer and award-winning journalist who was born in Kuwait and grew up in Egypt and the U.S. She’s currently at work on a novel.