Rabelaisian Enumerations: On Lists

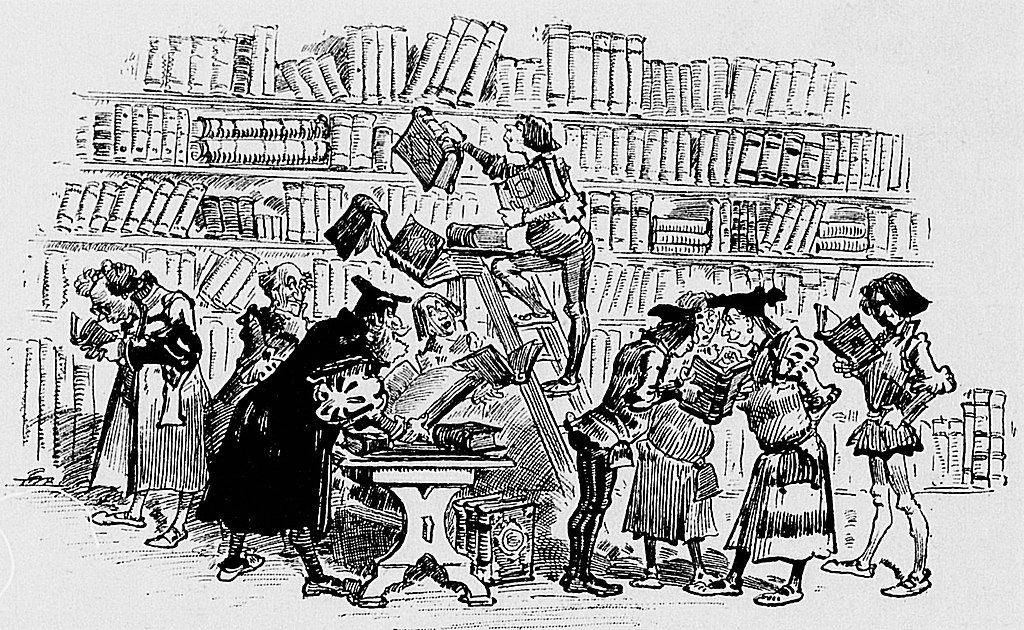

Illustration by Albert Robida, from chapter seven of Pantagruel (1886). Courtesy of the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Few are the authors whose names rise to the status of adjectives: Shakespearean profundity, Dickensian squalor, Kafkaesque bureaucracy. Rabelaisian—satirical, excessive, corpulent—joins these ranks. The French author François Rabelais’s first novel, Pantagruel, is a heady celebration of abundance in which sexual organs and epic feasts sit alongside scatological humor. Beneath the absurdity, however, is a deep critique of Renaissance learning.

The plot is simple: Pantagruel, a giant, grows up, gets an education in Paris, makes many friends, and ends up fighting to defeat the Dipsodes, a rival group of giants who have invaded Utopia. In an early chapter, the eponymous hero heads off to the University of Paris and stumbles upon the Library of Saint-Victor, which he finds “most magnificent, especially certain books he found in it.” What follows is a long list of rather odd titles, among them:

- Bregeuta iuris (The codpiece of the law)

- Malogranatum vitiorum (The pomegranate of vices)

- La couillebarine des preux (The elephant balls of the worthies)

- Decretum universitatis Parisiensis super gorgiasitate muliercularum ad placitum (Decree of the University of Paris concerning the gorgiasity of harlots)

- La croquignolle des curés (The curates’ flick on the nose)

- Des poys au lart cum commento (On peas with bacon, with commentary)

- Le chiabrena des pucelles (The shitter-shatter of the maidens)

- Le culpelé des vefves (The shaven tail of the widows)

- Antipericatametanaparbeugedamphicribrationes merdicantium (Discussion of messers and vexers: Anti, Peri, Kata, Meta, Ana, Para, Moo, and Amphi)

- La patenostre du singe (The monkey’s paternoster)

- La bedondaine des presidens (The potbelly of presiding judges)

- Le baisecul de chirurgie (The kiss-ass of surgery)

Usually, institutional libraries are governed by highly codified policies. Their catalogues are their raison d’être, elegant data structures that facilitate easy circulation and millennial continuity. Here there is none of that—the titles are solipsistic and self-referential, “codpieces” without organs, surfaces with no depth, skin with no substance.

This salmagundi (today this means “a dish of seasoned meats,” but the word comes from Rabelais’s Le tiers livre) gestures at some basic problems of information management: What sort of collection should a library hold? How should books be classified? What is the function of lists?

Lists are important because they manage our order of discourse. And because they are the heart of information systems, they teach us how data becomes knowledge. In Rabelais’s time, the old cosmology of medieval knowledge was dismantled piece by piece and reconstructed into the new constellation of the humanist encyclopedia. This state-of-the-art knowledge was then scattered far and wide by printed books. The historian Ann Blair has shown that this proliferation of books gave rise to the anxiety of “too much to know.” It was the newly invented printing press that inspired Rabelais to summon forth the incandescent trope of poetic enumeration.

***

The Renaissance also gave birth to the studiolo, the private study or personal library coveted by all well-heeled cultural elites. From Petrarch to Machiavelli, from aristocrats to cardinals, well-read humanists engaged in a gentle sort of competitive rivalry to curate a bespoke room of one’s own. The study was grounded in bibliophilia: a love of books, it was believed, uplifted the soul. Fiction responded by highlighting the negative side of bibliophilia. Some of the great characters in Renaissance literature have their lives upended by books: Don Quixote reads so many chivalric romances that he becomes mad; Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest is exiled to an island on account of his readerly obsession; Doctor Faustus spends too much time in his study and sells his soul to the devil. In an era of discoveries and upheavals, these bibliophiles’ readings and identities are so entangled that they lose their grip on reality. Overwhelmed by the confusion of atlases, catalogues, and encyclopedias, they take their world to be their library, and the library to be their world.

Pantagruel shares with these book-besotted men an epistomania, an overwhelming appetite for knowing it all. My sense is that Don Quixote, Prospero, and Faustus were invented to show how noble minds can be overthrown by their own libraries. But Pantagruel is quite different from this distinguished company, for Pantagruel enters an institutional library—and only briefly at that—and exits unscathed.

In the thirteenth century, the University of Paris emerged as the leading center for scholastic philosophy in Western Christendom, in no small part due to the contribution of the Abbey of Saint-Victor. In 1114, William of Champeaux, after a long and brilliant career at the school of Notre-Dame, settled in an abandoned hermitage outside the city walls and founded a community of canons in honor of Victor, a fourth-century saint. The abbey quickly became distinguished for its erudition.

The Book of Orders, written around 1116, gives us a sense of what life was like inside the abbey. The monks lived in an environment in which every micromovement—from waking, sleeping, eating, walking, and standing, to praying—was precisely and strictly regulated. To this regime of absolute control Giorgio Agamben has devoted a slim book: The Highest Poverty (2013) reconstructs how the imposition of order undergirds the entire infrastructure of Western monasticism. Agamben calls the monks’ obsessive restrictions on what to do and how to do it a “form-of-life” in which “form” and “life” become inseparable. “What is a rule, if it seems to be mixed up with life without remainder?” he asks. “And what is a human life, if it can no longer be distinguished from the rule?”

One of the most important regulatory roles in the Victorine community was that of the armarius, the librarian. He possessed “in his custody all the books of the church.” He dictated the common readings and chants for all occasions, “whether at Matins, at Mass, at chapter, at the table, or at collation.” As it happens, posterity has bequeathed to us Saint-Victor’s library catalogue from 1514. The armarius at that time, Claude de Grandrue, made a list of the Abbey’s 1,081 manuscripts and did some innovative things: he inscribed an “ex libris” at the beginning of each volume, foliated every page, and assigned a pressmark to indicate its location. The books were then arranged in an alphabetical sequence: A–Z, AA–ZZ, AAA–OOO. Here is a sampling:

A: The Old and New Testaments, usually with the Glossa ordinaria

B: The New Testament, biblical concordance, works on the Bible by Pierre le Mangeur, Jean Marchesini, Adam of Saint-Victor, Pierre Riga; Greek and Hebrew Psalters, Greek Gospels

C–F: Commentaries on the Scriptures

G: The works of Albert the Great

H: Albert the Great, Thomas Aquinas

K–M: Commentaries on the Sentences of Peter Lombard and theological questions by Alexander of Hales, Bonaventure, Giles of Rome, Guillaume d’Auvergne

N–Q: Canon Law, Gratian’s Decretum, writings by Yves de Chartres, Bernard of Compostella, Baldo Ubaldi; documents on the Great Schism; the councils of Constance and Basel; handbooks on notaries; manuals on epistolary

R–S: Civil law, texts and commentaries, barbarian laws, feudal laws, customs of Normandy

T: Medicine, texts and commentaries (Galen, Avicenna, Hippocrates, Arnaud de Villeneuve, Guy de Chauliac, et cetera)

But by the time of Rabelais, such knowledge systems must have seemed superannuated, and thus ripe pickings for satire. The author’s entire apparatus aimed to topple such strict hierarchies. His exuberance erupts from these rigid boxes of knowledge; he crafts instead a cunning poetics of infinite enumeration. Who else would come up with Three Books on the Mensuration of Army Camps in the Hair; Hotballs [chaultcouillons], On the Guzzling-Bouts of Doctoral Candidates and Doctors: eight highly lively books; The Fart-Volleys of the Bullists, Copyists, Scriveners, Brief-Writers, Referencaries, and Daters, compiled by Regis; or Marforio, a Bachelor lying in Rome, On Skinning and Smudging Cardinals’ Mules? His salty catalogue mocks the Faculty of Theology and its hairsplitting scholastic ratiocinations, and skewers the vices and laziness of the clergy. Rabelais was the perverse librarian par excellence.

***

Yet this list is a parable of not just medieval pedantry but early modern information overload. Across Europe, books about books proliferated: publishers offered seasonal lists; owners catalogued their collections; censors compiled indexes of prohibited books; auction inventories were drawn up for the estates of the deceased. But is not a random collection of titles—no matter how clever—too tiresome for the reader? Does not the multitude of names lead to tedium or frustration, and therefore to skimming or skipping?

In the Middle Ages, Noah’s ark was the emblem of the total archive. In fact, bibliographers and Noah have many things in common. They must contend with the problem of inclusion, inventory, and survival. Like animals, manuscripts can multiply. In the Bible, Noah’s ark offers safe passage to every creature great and small. But were there some that didn’t make the evacuation? In that sense, Rabelais is Noah 2.0: not only does he include all the books that have ever existed, but he includes even those that do not exist. Like Noah, Rabelais suffers from the pathology of accumulation.

Along with the ark, Rabelais uses another figure: the abyss. The word appears twice in other parts of the book: “an abyss of science” and “the true well and abyss of the Encyclopedia.” The logic of enumeration, pushed to its extreme, becomes an algorithm of the absurd. Rabelais points out that there are oddities in the world that cannot fit into any classification scheme, more things in our heaven and earth than are dreamt of in either the medieval pretensions of the summa or the ambitious early modern bibliographic machines. The abundance of the information ark becomes an encyclopedic abyss.

It is only from this historical condition of data glut that characters like Pantagruel, Don Quixote, Prospero, and Doctor Faustus could have emerged. Though the topos of multitudo librorum—too many books—existed already in antiquity, the proliferation of texts brought on by the printing press was unprecedented. That these characters are all driven to bibliomania suggests their inability to cope with cognitive inundation. They show the tragedy of reading too much, and too wrongly. It is only Pantagruel who exits the library laughing.

***

Every cultural action has an equal and opposite reaction. The bibliographers and the censors existed side by side. At the exact same time that bibliophiles were churning out lists telling people what to read, a countervailing force pushed back: bibliophobia. Church authorities were churning out lists of what people should not read.

One of the first counterblasts to the Reformation was the Catholic Church’s creation of the Index of Prohibited Books. Pantagruel had the honor of making the list. In 1533, less than a year after its publication in Lyon, the book was denounced by the authorities; a revised edition in 1543 expurgated some of its racier bits. In 1551 the Sorbonne published a list of censored books that included editions of Pantagruel, Gargantua, and Le tiers livre. The Council of Trent placed Rabelais at the head of the “heretics of the first class.” As soon as each of his four books appeared in print, they were condemned by the French authorities.

The creator of any list endlessly negotiates the desire to submit and to control, to surrender and to order. The Roman censors’ knowledge was parasitic: they used the very same works that they condemned to compile their own lists. For example, a library in Bologna possesses a copy of Conrad Gesner’s Bibliotheca instituta et collecta once owned by zealous Jesuit, Antonio Possevino. It is heavily annotated, and Possevino used Gesner to create his own guide, called the Bibliotheca selecta. As the title implies, he selected for the reader texts that are in absolute conformity with church doctrine. What is interesting is that the Jesuit and Gesner both cancel and supplement each other. They both try to direct the reader to what is worthwhile and what is not. The bibliographer creates metaknowledge, whereas the censor suppresses it.

So between the Scylla of classification and the Charybdis of suppression, Rabelais avoids a shipwreck by deploying what he knows best—excess. He bypasses this bibliographical conundrum by presenting fake books. How can you be censored if you don’t have any content?

***

In Jorge Luis Borges’s “Library of Babel,” readers can find:

The detailed history of the future, the autobiographies of the archangels, the faithful catalogue of the Library, thousands and thousands of false catalogues, the proof of the falsity of those false catalogues, a proof of the falsity of the true catalogue, the gnostic gospel of Basilides, the commentary upon that gospel, the commentary on the commentary on that gospel, the true story of your death, the translation of every book into every language, the interpolations of every book into all books, the treatise Bede could have written (but did not) on the mythology of the Saxon people, the lost books of Tacitus.

With Babel, we come full circle back to the ark. Like Rabelais, Borges wants to know and have it all—in fact, the moral of the story is that our dream of the total library is actually our deluded desire to become gods. In the Bible, the ark and the Tower of Babel are survival machines that protect humans from divine calamity. Totality and ruin, humans and God, proliferation and confusion—these are the grand themes of the Bible and the history of imaginary libraries.

Lists beget lists. But they also cannibalize one other. In fat years, we make lists to keep track of what we have. In thin years, we make lists of what we had or what we want. They give us a measure of comfort and hope. And in good times and bad, we make lists of invented books to remind us of our finitude.

From The Study: The Inner Life of Renaissance Libraries, to be published by Yale University Press in December.