Lead In The Water And Chloroprene In The Air: Who Does The Epa Protect?

Who does the EPA protect?

The Biden administration promised change for overpolluted communities in the South. Four years later, they’re still waiting.

By Lylla Younes Jan 16, 2025When President Joe Biden announced his Justice40 Initiative, a week after he took office in January 2021, it had been almost 30 years since a U.S. president had signed an executive order related to environmental justice. He directed the federal government to allocate 40 percent of the benefits of climate, clean energy, and other investments to disadvantaged communities “marginalized by underinvestment and overburdened by pollution.”

Biden’s initiative was a kind of rejoinder to President Bill Clinton’s earlier executive order, which directed federal agencies to identify and address the adverse human health and environmental effects of their actions on minority and low-income areas. While much toxic pollution was curbed in the decades in between, for the parts of the country with the highest concentrations of industrial activity, things hadn’t improved at all. More industrial companies set up shop. Dump sites swelled. Contaminated rivers became more contaminated. Lead accumulated in the soil. Biden’s Justice40 Initiative gave his new Environmental Protection Agency administrator, Michael Regan, the task of not looking away.

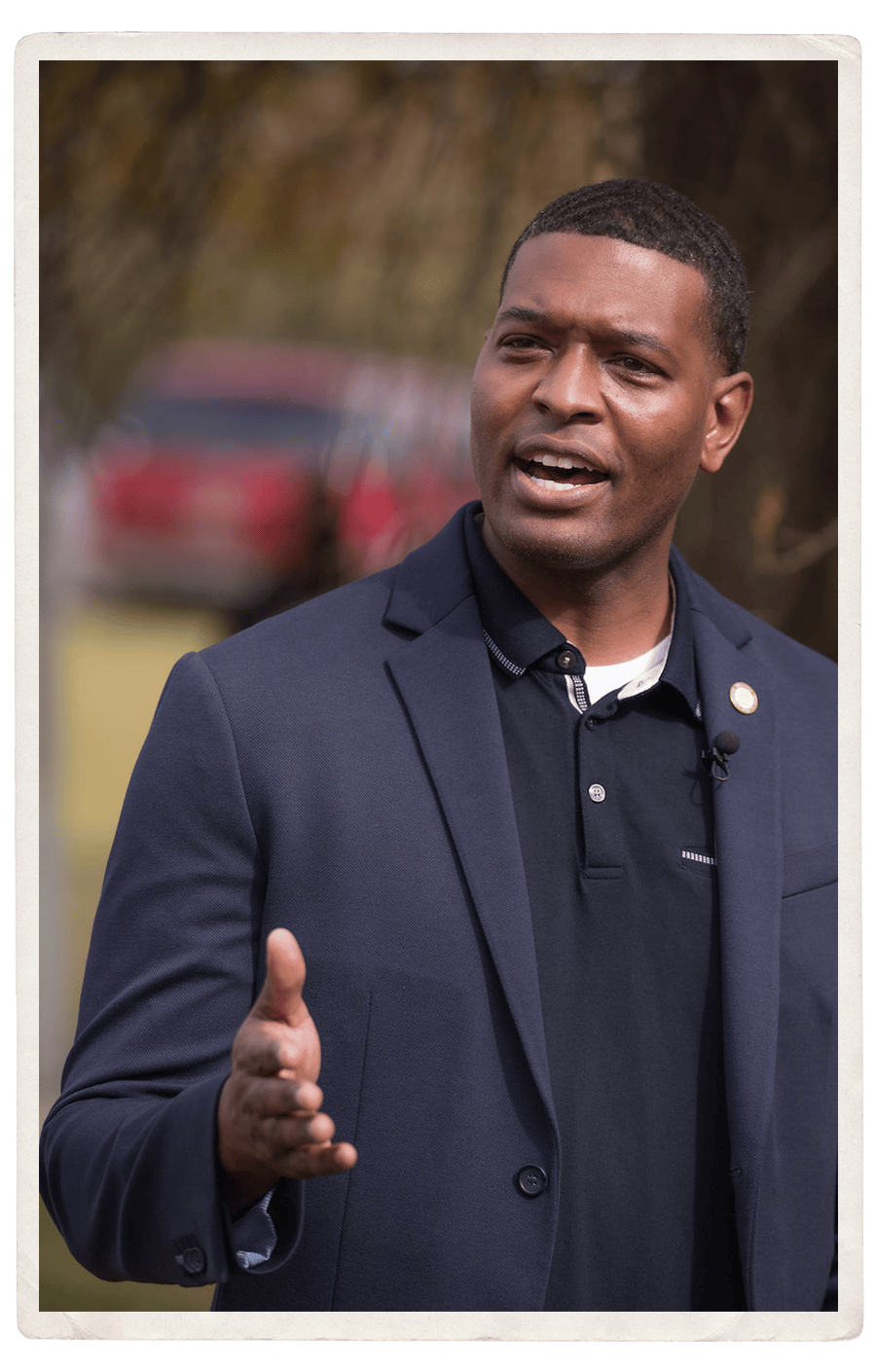

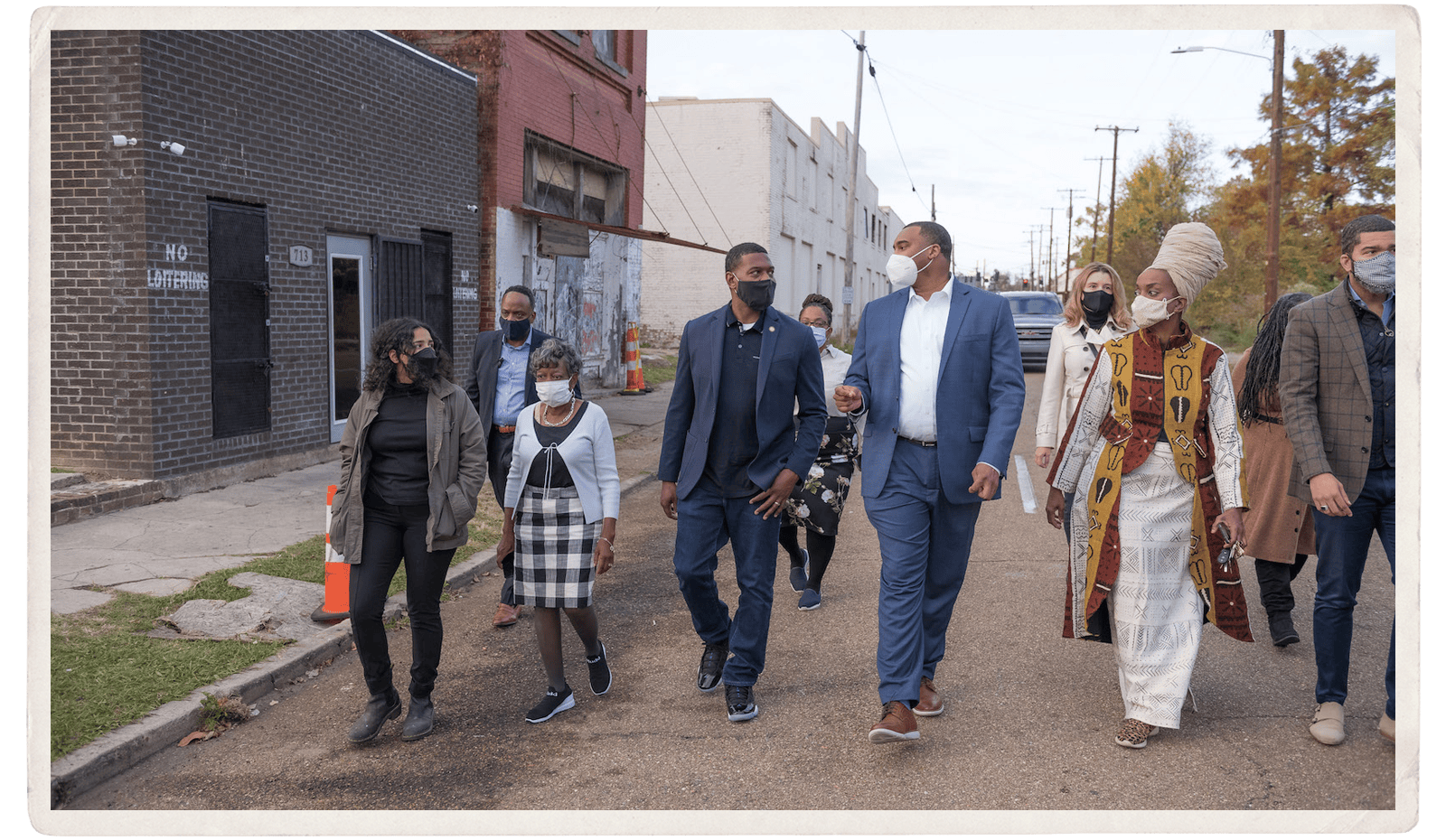

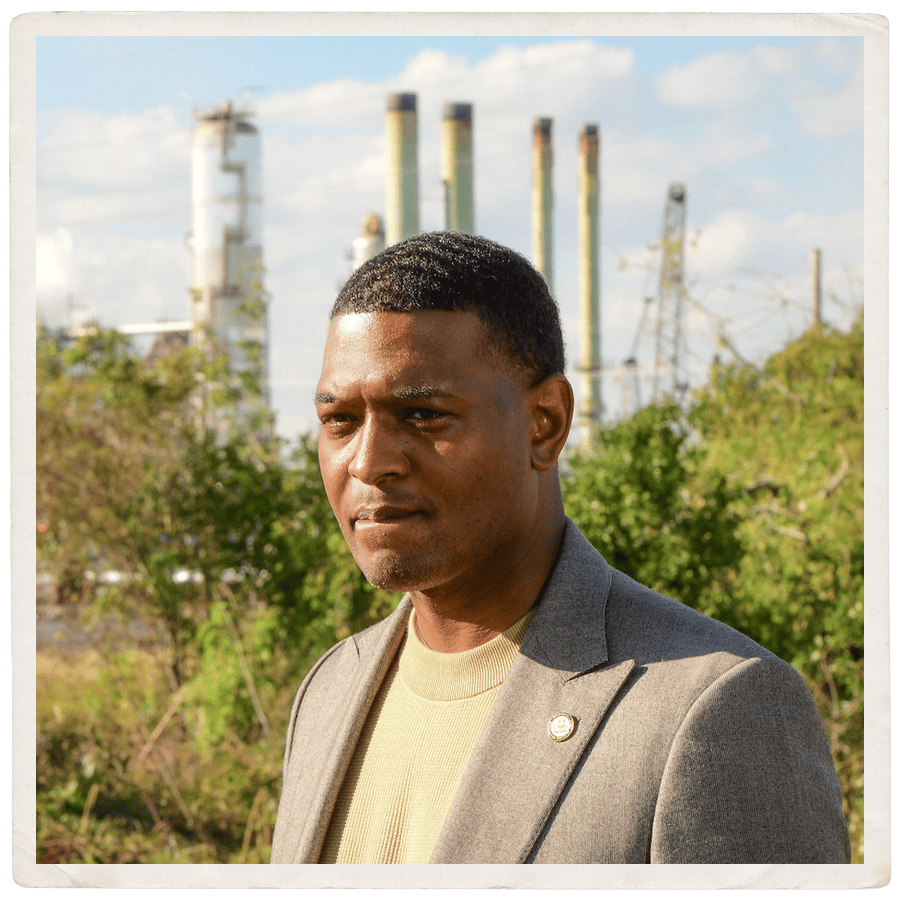

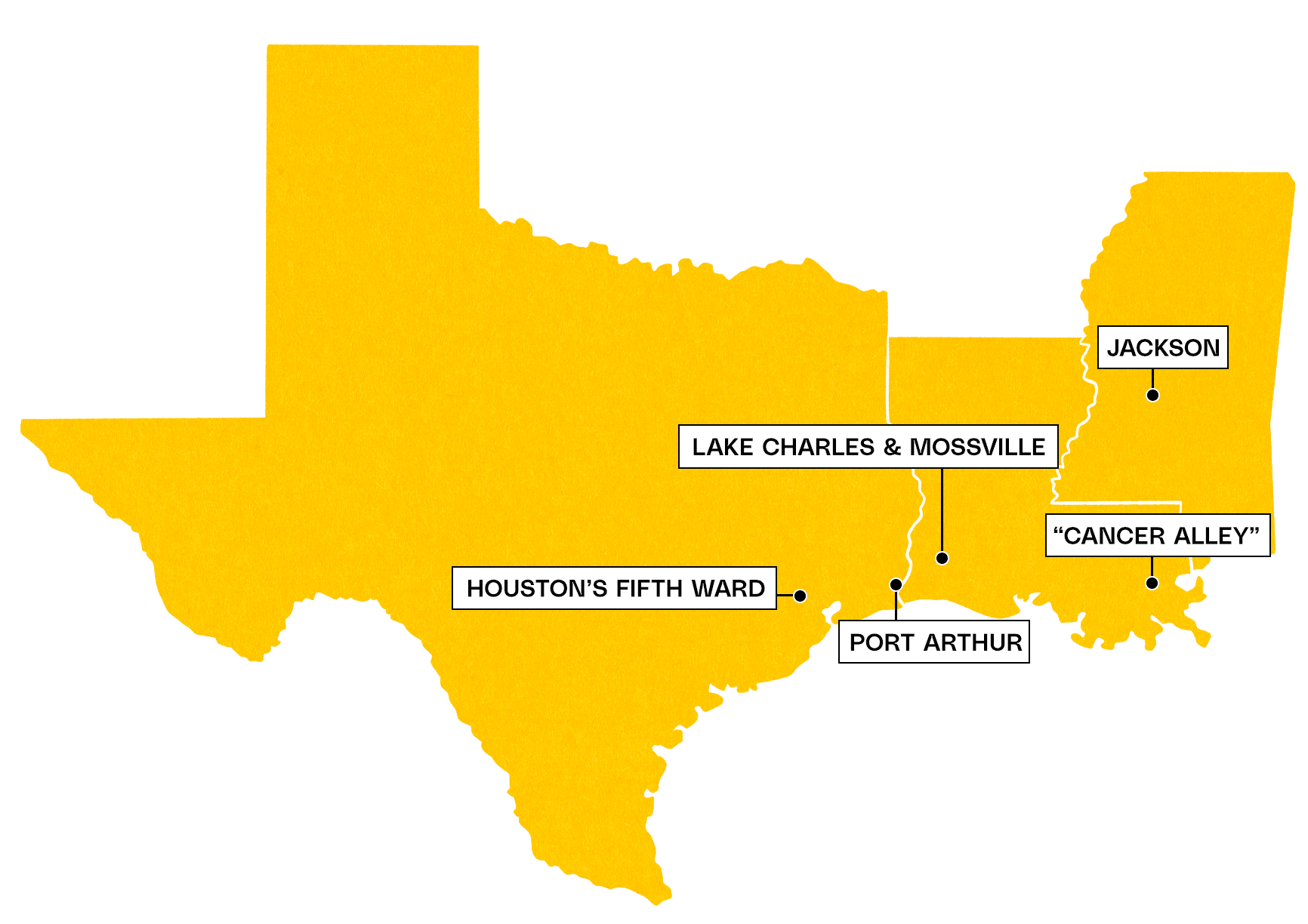

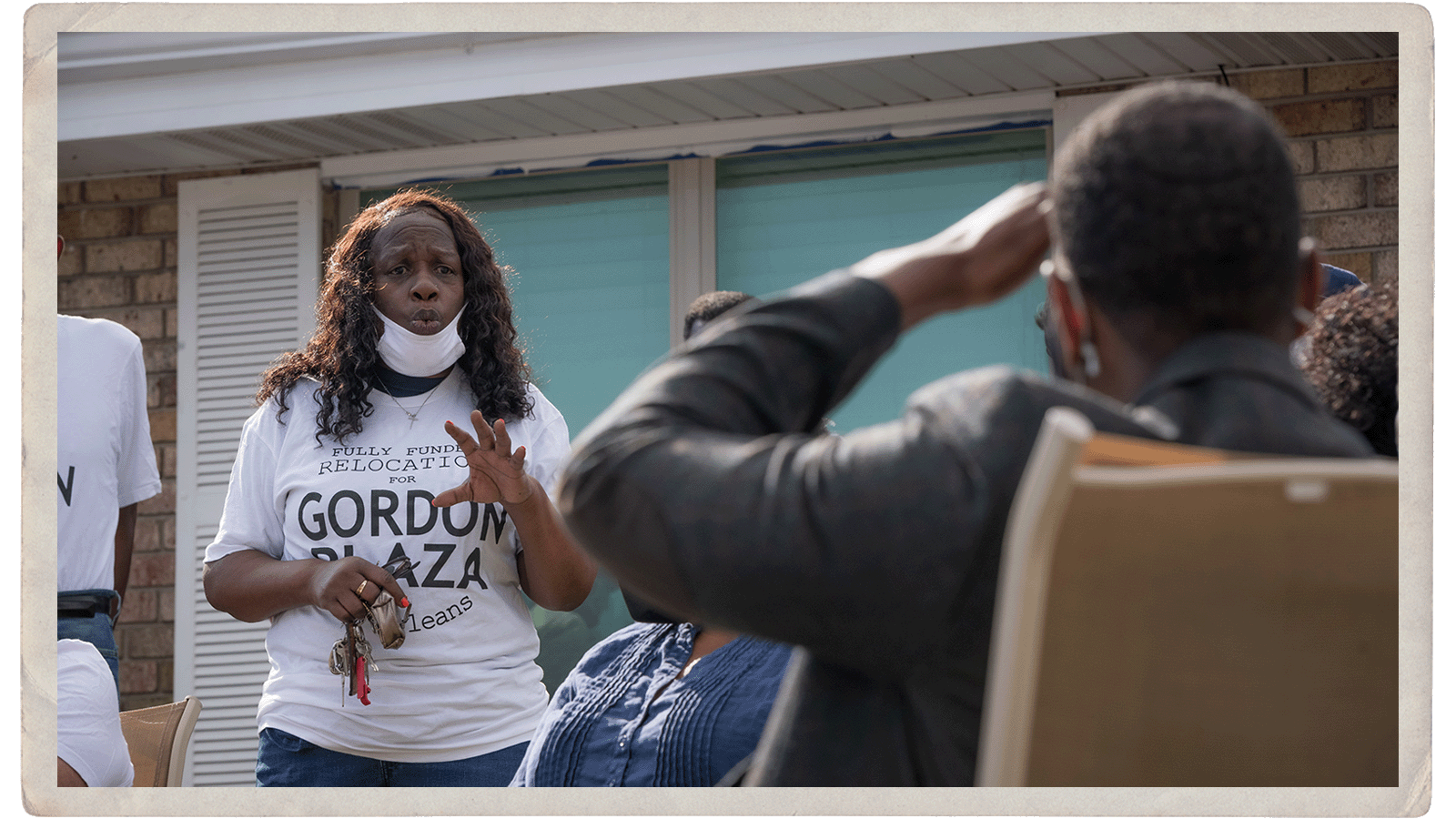

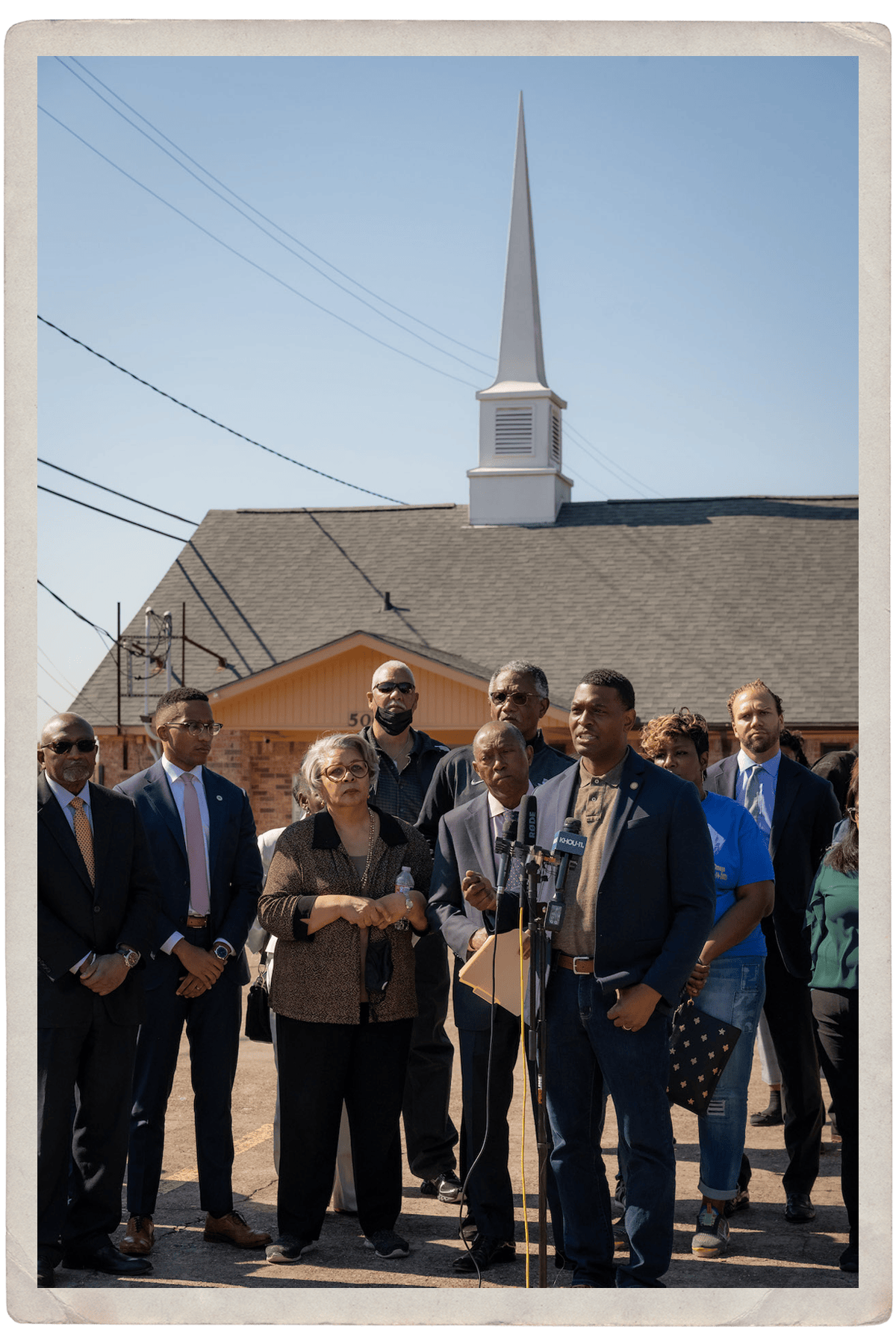

In November 2021, as if to signal that the EPA had turned a leaf, Regan embarked on a tour of Southern towns and cities where the problem of environmental injustice is most acute: Jackson, Mississippi; Cancer Alley and Mossville in Louisiana; Houston, Texas. Dubbed the “Journey to Justice,” he met with community leaders and residents whose testimonies he promised he’d take into account when he returned to Washington.

“[The tour] was really eye-opening,” Regan said in an EPA documentary about the trip. “To see it, to feel it, to have conversations. … I saw on the ground people expressing a desire to be treated like everyone else.”

This fall, I set out to retrace Regan’s tour and look for signs of whether and how much the struggle for environmental justice truly advanced under Biden and Regan. Having reported on the region and the EPA’s operations there for six years, I knew that in its most polluted areas, changing conditions on the ground would take longer than a presidential term; still, I wondered whether the immediate actions that residents say they need — fines for companies violating federal standards, home buyouts with fair prices, permit reform, more government transparency — had been granted.

I knew that this iteration of the EPA was a test — of the limits of American bureaucracy, of the strength of industrial and corporate power, of the purpose and efficacy of the EPA itself.

No previous administration had dedicated enough resources, funds, or public relations efforts needed to confront industry’s unbridled expansion in the country’s most polluted and vulnerable areas. Cleaning up America’s air and water, a bipartisan mission at the EPA’s founding in 1970, has become highly politicized over the years, with reactionary state governments and industrial companies balking at the agency’s attempts to tighten regulations — all of which makes it difficult to imagine another administration, especially one led by Donald Trump, continuing these efforts.

Over 500 miles, through thick swampland and crowded interstate highways, I encountered scenes and people that elucidated the promise of Biden’s environmental justice agenda — and where it fell short. The administrator’s visits raised the profile of these industrial sacrifice zones and spurred EPA efforts to strengthen industrial regulations. But many community leaders remained frustrated at the agency’s hesitation to push for more aggressive, systemic change. Policies like permit reform and deepening community engagement could have helped safeguard the progress of the past four years against the whims of President-elect Donald Trump and his incoming administration, which has promised to clear the path for unchecked oil and gas production. Indeed, over the course of the Biden EPA, the agency’s core function was exposed. So were its limits.

Regan began his Journey to Justice tour in Jackson, Mississippi, on the same day in November 2021 that Biden signed the first of his two landmark climate bills, the bipartisan infrastructure act, into law. The capital city is at the end of a long period of decline. In most of its neighborhoods, tangles of overgrowth spill onto wide, empty streets bearing cracks and potholes. Torn up segments of asphalt and caution tape are ubiquitous. All across south and east Jackson, abandoned homes appear to be overtaken by the land, the roofs fallen in, the windows all gone, vines threading up the exteriors as if to pull the structures back down into the earth.

The city, which is more than 80 percent Black and has a poverty rate more than double the national average, is also in dire need of extensive infrastructure upgrades to its water system — an issue within the remit of the EPA. As Biden and Regan were just taking office, a quick succession of severe winter storms caused systemic failures at one of Jackson’s primary water treatment facilities. About 20,000 customers served by the O.B. Curtis plant — 15 percent of the city’s population — lost access to safe, reliable water.

The facility lacked proper weatherization equipment and suffered from a lack of corrosion controls, which allowed bacteria to spread throughout the system. By November, the city’s water distribution network was plagued by persistent leaks and lead contamination, and the whole system was nearing a breaking point. Rolling boil-water notices advised residents of E. coli contamination, which causes stomach pain and can lead to kidney damage. Additionally, two separate lawsuits filed by aggrieved parents blamed the city for their children’s lead poisoning diagnoses. One of Regan’s first stops in Jackson was to tour the Curtis plant with Jackson’s mayor, Chokwe Antar Lumumba, and Charles Williams, the city’s Public Works director. He pledged later that day to ensure the community, and others like it, would get the funds they needed to address infrastructure failures endangering public health.

A water tower, left, looms over an abandoned soy depot in Jackson, Mississippi. In another part of town, right, vines overtake old buildings. Lylla Younes / Grist

Later in the day, after his visit to Wilkins Elementary School, which was enduring low water pressure, Regan championed Biden’s infrastructure spending as a solution to environmental injustice. “We want those who need these resources the most to receive them first,” he said. “So we’re going to work very diligently with our state partners to ensure that, in months not years, communities like Jackson will be able to receive the funds and move forward with investing the funds.”

In January 2022, just a few months after Regan’s visit, the EPA issued a notice of violation to the city for failing to comply with the terms of the Safe Drinking Water Act, requiring local officials to develop a corrective action plan. In August, heavy rainfall caused the pumps at O.B. Curtis to fail again. Water pressure throughout the network plunged, and the entire city was without potable water. Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves declared a state of emergency. Pictures of Jacksonians waiting in long queues for National Guardsmen to load crates of water bottles into their cars flashed across national headlines.

Regan visited Jackson twice in quick succession. “It’s hard to explain how and why [the] government has failed the city of Jackson and the people of Jackson,” he said in an October interview. When asked whether he would consider implementing “a state or a federal takeover of the Jackson water system,” Regan replied, “We’re evaluating all options.”

By November, the EPA’s complaint against Jackson for violating the Safe Drinking Water Act ended up in federal district court, where Judge Henry Wingate issued an order appointing Ted Henifin, an engineer known for his experience overhauling municipal water infrastructure, to manage the system. Several weeks later, the Biden administration allocated an unprecedented $600 million to fix the city’s beleaguered water infrastructure. Something like a takeover was beginning to take form, and it was a moment of great hope for a city that had suffered decades of white flight and discriminatory neglect.

But in the years since, Jackson’s water troubles have become not only a crisis of public health, but also one of public trust. A wide cast of characters continues to vie for control of both the system and the narrative, and ordinary people are left wondering about the true state of affairs. In 2023, Henifin created a private company named JXN Water to carry out the overhaul of the city’s water system, and through which all of the federal money is funneled. It was a move that only worsened the issues of trust. The EPA, for its part, has been sidelined in a process it created.

In August 2022, after heavy rainfall, Jackson’s water system failed again and lurched toward a breaking point. Residents, meanwhile, relied on bottled water.

In August 2022, after heavy rainfall, Jackson’s water system failed again and lurched toward a breaking point. Residents, meanwhile, relied on bottled water.Brad Vest / Getty Images

I arrived in Jackson on a rainy night last October, about a week before the presidential election. Momentarily forgetting the purpose of my visit, I opened the kitchen tap at my rental to fill a glass of water and was immediately hit with the stench of rotten eggs. I stood by the sink with the tap running for a moment longer, shocked by how quickly I had encountered the very problem residents had described to me on the phone over the past year. Then I noticed the tall water dispenser in the corner.

“You’re on a war boat declaring the mission’s been accomplished, but bombs are still dropping,” local activist Makani Themba told me the next morning, referring to President George W. Bush’s infamous speech about the war in Iraq.

That, she continued, was what it has felt like to have the federal government swoop in to address the failing water system, only for the problems to persist.

We were chatting at Themba’s kitchen table. She has warm eyes and curly snow-white hair, which she’d gathered in a high bun. That day, she and other local advocates were still reeling from a recent hearing in which Judge Wingate accused them of being racist against Henifin, a white man, for challenging his governance of the water system. All they’d been agitating for, Themba said while stirring a pot on the stove, is transparency and community engagement. She and other activists had initially been excited about the engineer, having heard from environmentalists in St. Louis that he had worked miracles there. But instead of a collaborative process, many Jackson residents and activists were shut out once Henifin established his private company to fix the city’s drinking water problem.

According to Jackson activist Makani Themba, the federal government swooped in only for the problems with the failing water system to persist. Lylla Younes / Grist

According to Jackson activist Makani Themba, the federal government swooped in only for the problems with the failing water system to persist. Lylla Younes / Grist“I wish that the EPA’s behavior here in Jackson would reflect the goals and the principles that the Biden administration laid out,” Themba said. “They talk about community involvement and all these things, but that’s not what we’ve experienced.”

“I’d say right now we’re in the worst position we’ve possibly been in since the EPA stepped in to help us,” said Tariq Abdul-Tawwab, the director of the Mississippi Rapid Response Coalition’s ground support team, which has been instrumental in mobilizing bottled water, filters, and lead testing kits to Jackson residents. Reflecting on the hearing with Judge Wingate, he continued, “When you’re being told you don’t have the right to ask questions, it’s the beginning of the end.”

Outside the realm of advocacy and politics, the water crisis has become a part of daily life. Willie Williams, the owner of the local restaurant Sweet Spot, pays a monthly bill to upkeep a water filtration system he installed, because he can’t serve or cook with the tap water.

“It’s more than a crisis. I mean, it’s something that you have to add to your budget when you’re a business owner,” he said. “Water is very important.”

Another Jackson resident, Lula Henry, who I’d been connected with by a member of the Mississippi Rapid Response Coalition, had recently come home to find her washroom and carport flooded after a group of city contractors blew open a hydrant while working on her street. When I pulled up to her house, furniture and cooking equipment lay scattered throughout the front yard, drying off in the sun. Like other residents I spoke to, Henry only uses the tap water in her house for cooking and bathing, and relies on bottled water for drinking and brushing her teeth. She called JXN Water to understand what happened. No one came to help.

The drive from Jackson to south Louisiana takes about three hours, and shortly past the state line, the strips of pine forest flanking the highway give way to extensive swampland. After crossing the freshwater marsh at Lake Maurepas, I was finally in “Cancer Alley,” a stretch of land on the lower Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans where over 200 industrial facilities operate in the vicinity of historic Black neighborhoods. Recent studies have confirmed what residents of the region have long said, that people living along the fence lines of these industrial operations suffer from higher-than-average rates of miscarriages, infertility, respiratory ailments, and cancer.

Under the system of air pollution regulation in the U.S., fighting the construction of new industrial facilities is difficult. Cleaning up existing ones is even harder. Amendments to the Clean Air Act passed by Congress in 1990 divided the country’s industrial landscape into different categories of facilities and gave the EPA a decade to develop a set of regulations for each. It was a momentous task that required agency staffers to collect emissions data for thousands of plants across the country and determine what technologies industrial companies should install to reduce the pollution. These new rules, while useful for reducing — though not eliminating — emissions from facilities without pollution controls, could only work at the margins of the health crisis taking shape in the country’s most industrial areas. As toxicologists often point out, in the case of potent cancer-causing chemicals like dioxins, no level of exposure is considered safe.

“There’s nothing in the Clean Air Act itself that says a community has a right to be healthy and safe,” said Monique Harden, a former director at the Deep South Center for Environmental Law and Policy. “It’s a voluminous and very technical document that puts into law the status quo of industrial operations.”

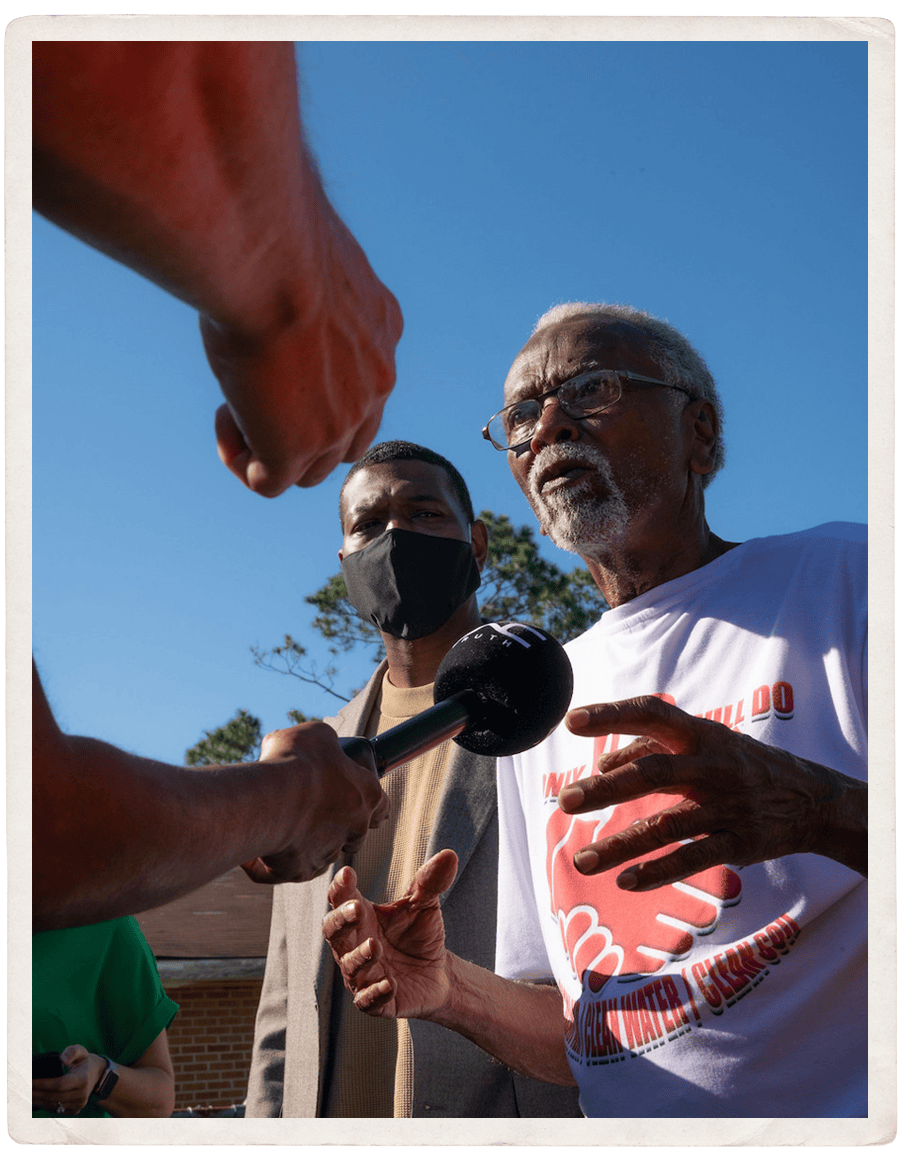

As part of his 2021 tour, EPA administrator Michael Regan speaks to residents of “Cancer Alley,” where over 200 industrial facilities operate in the vicinity of historic Black neighborhoods.

As part of his 2021 tour, EPA administrator Michael Regan speaks to residents of “Cancer Alley,” where over 200 industrial facilities operate in the vicinity of historic Black neighborhoods. EPA

Scott Throwe, who spent 30 years working in the EPA’s enforcement division, remembers the 1990s as a time of great activity and immense pressure. Agency staffers were directed to write rules that wouldn’t generate much public comment controversy or lead to lawsuits from chemical companies. In their rush to finalize all the rules by statutory deadlines, certain community health protections fell through the cracks.

“It’s like watching a sausage get made. It’s not pretty, and we made a lot of sacrifices,” he recalled. “We couldn’t get perfect rules out, and sometimes they weren’t even very good. They were just OK.”

The amendments to the Clean Air Act also directed the EPA to revisit the slate of rules after eight years to assess the cancer risk that remained in communities. Many of these “risk assessments” were conducted under George W. Bush’s EPA, which adopted a far less protective standard of acceptable risk than prior administrations. Whereas the original text of the Clean Air Act said the EPA should strive to protect the public from pollution exposure with a cancer risk greater than 1 in 1 million, the Bush EPA began using the exponentially less protective standard of 1 in 10,000.

While the Bush standard may seem fairly protective on its face, agency assessments only evaluate the cancer risk from a single chemical at a time. In reality, though, multiple plants operate simultaneously and in close proximity, releasing a slew of toxic chemicals on surrounding communities. The true cancer risk is cumulative.

The task, then, of enforcing these standards lies with state governments. Regulators in state agencies have wide latitude to permit new industrial facilities, along with construction and operating permits, wherever they see fit, including in areas that are already highly polluted.

When Regan came to Cancer Alley in November 2021, he visited Fifth Ward Elementary in St. John the Baptist Parish. The school sits in the shadow of the Japanese chemical company Denka’s synthetic rubber manufacturing plant. Regan told residents that the proximity of the facility’s toxic chloroprene emissions to the school reminded him of his young son, and that the trip compelled him to use his “bully pulpit” to make change.

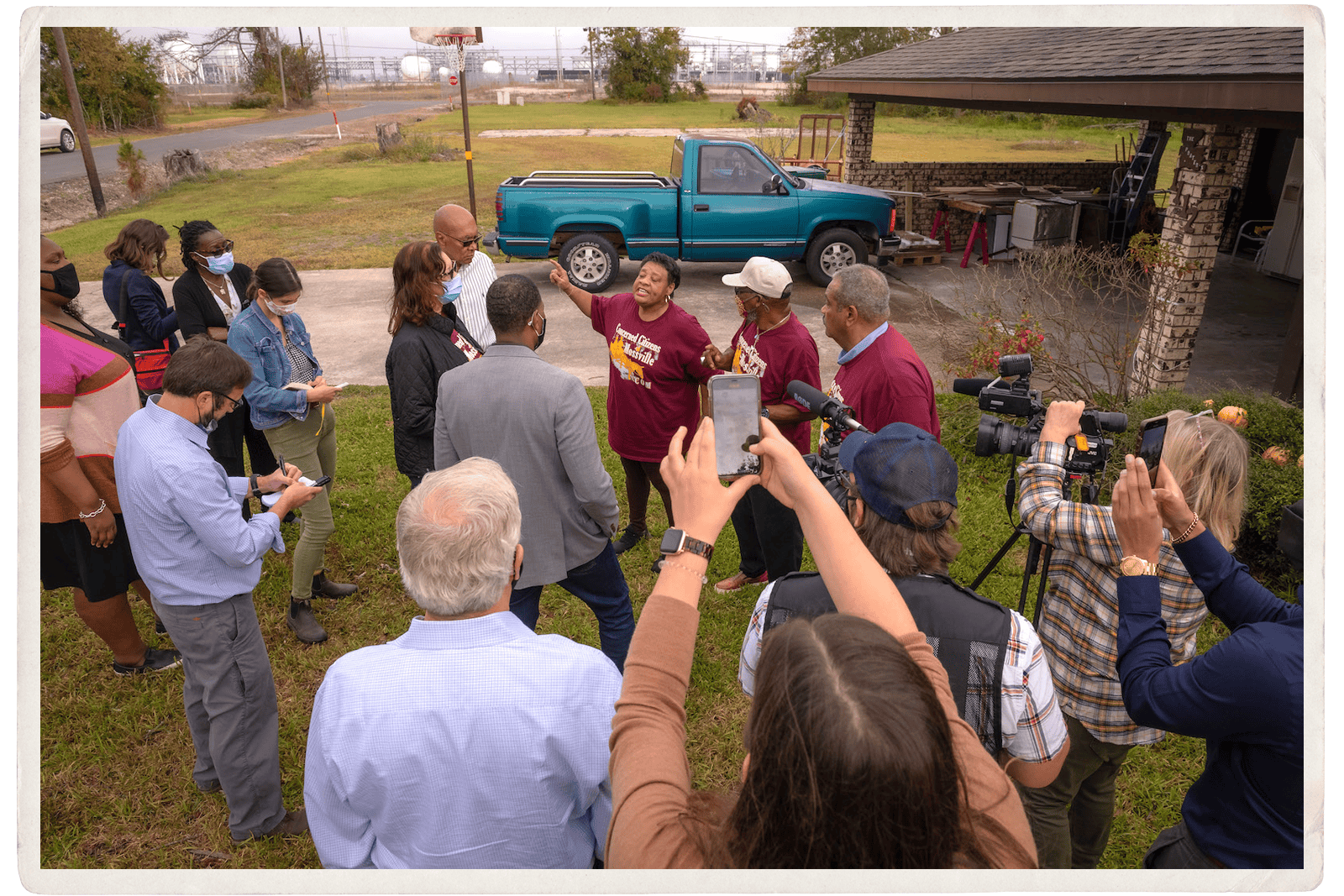

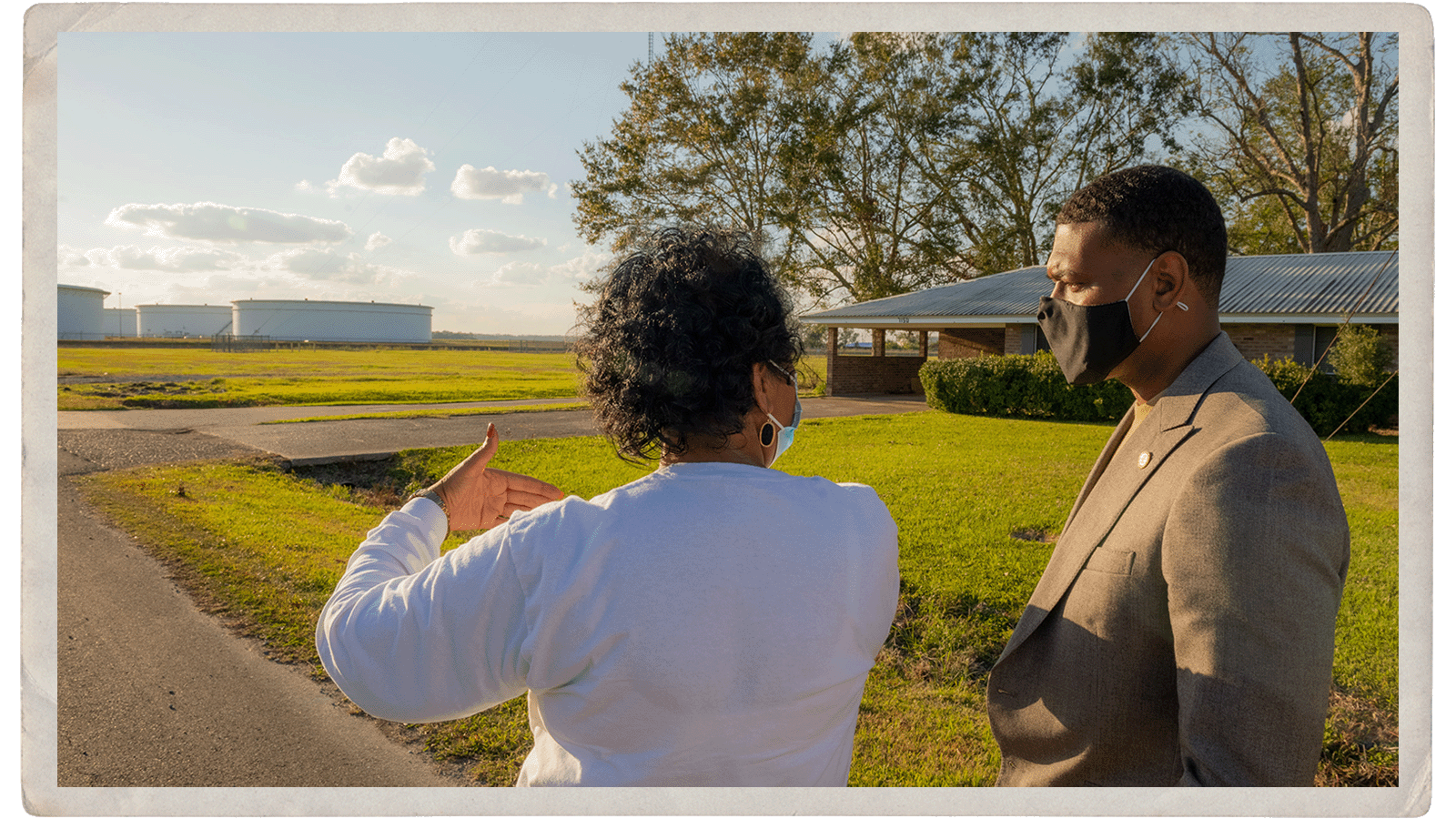

Later, Regan left for a tour of nearby St. James Parish. Among the group of activists, local residents, and reporters there to receive Regan and his staff was Sharon Lavigne, a local organizer. When he emerged from his travel bus, the sight of a sharply dressed Black man around the age of her son shocked Lavigne.

“I thought it would have been an all-white man with gray hair,” she said. “He was good-looking!”

When Sharon Lavigne met Regan in 2021, the sight of a sharply dressed Black man shocked her. “He was good-looking!” she said.

When Sharon Lavigne met Regan in 2021, the sight of a sharply dressed Black man shocked her. “He was good-looking!” she said.Eric Vance / EPA

Regan expressed surprise at how close chemical storage tanks were to people’s homes. The administrator promised to buff up the EPA’s inspections of local facilities and require certain companies to install air monitors around their facilities.

In early 2022, Lavigne’s organization, Rise St. James, and several other local environmental groups filed two separate civil rights complaints with the EPA. One complaint alleged that the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality, or LDEQ, had behaved discriminatorily by granting permits to companies to build in the parish’s Black neighborhoods, such as the Taiwanese chemical group Formosa’s proposal for a plastics complex in St. James Parish. The other contested the state’s decision to let Denka continue operating in St. John, despite the EPA’s own data showing that the cancer risk it generated violated federal standards. During previous presidential administrations, the EPA had allowed such complaints to languish unresolved, but under Regan’s leadership, the agency opened a civil rights probe into conditions in Cancer Alley.

Lavigne visits the graveyard where many of her friends are buried in St. James Parish. Lylla Younes / Grist

Lavigne visits the graveyard where many of her friends are buried in St. James Parish. Lylla Younes / GristFederal and state officials were making significant progress at the negotiating table in the early part of 2023. Louisiana officials agreed to assess pollution levels in communities before greenlighting new industrial development. But then Attorney General Jeff Landry (who’s now governor of the state) sued the EPA and the Department of Justice, arguing that they were overextending their authority. A month later, the EPA closed its investigation.

To Lavigne, the EPA’s handling of the civil rights complaints constituted a genuine attempt at improving conditions in Cancer Alley. Others I spoke to weren’t so generous. Lifelong St. James resident Melvin Whittington said the EPA’s actions in the region amounted to little more than “a front to make you think they’re doing something, but they’re not.”

With the civil rights probe closed, the EPA has run up against the extent of its power to do anything about the alleged discrimination in Formosa’s permitting. As for Denka, an EPA lawsuit against the company has been slowly making its way through the court system while the facility continues emitting the highly carcinogenic chemical chloroprene. In June, the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund sued the St. John the Baptist school board for violating its Civil Rights-era desegregation order by exposing the majority-Black student body to Denka’s toxic pollution — a tactic that exposes why the dynamics inherent to the hopeful phrase “environmental justice” are sometimes referred to with the more unforgiving phrase “environmental racism.”

Melvin Whittington, left, said the EPA’s actions in Cancer Alley amounted to little more than “a front.” Whittington lives near the Denka synthetic rubber manufacturing plant, right. Lylla Younes / Grist

Considering these developments, Whittington wondered aloud whether the organizing they’d committed themselves to in Cancer Alley had even been effective. His words seemed to echo the sentiments of residents I’d spoken to in Jackson, who’d said that for all the resources and attention from the EPA, meaningful change was still elusive. “Doesn’t seem like we’re getting nothing done,” he said.

Five days after I left Cancer Alley, the St. John school board voted to shut down Fifth Ward Elementary.

On the morning of Election Day, I headed west toward Lake Charles, Louisiana, passing through sprawling fields of soybean and sugarcane under an overcast sky. The serpentine Calcasieu River forms the city’s northern border, and across it lie the industrial town of Westlake and the community of Mossville.

I’d been here before, back in 2021, when I sat on the plush couch of Debra Sullivan Ramirez’s dimly lit living room, just a month before Regan’s tour. Sullivan Ramirez grew up in Mossville and moved to the city of Lake Charles in the late 1980s to get her three children away from the pollution, which she attributed to the lesions that had formed on their skin. As I sat with Sullivan Ramirez and two of her friends, discussing the string of diseases that had stalked her family, she handed me a stack of documents she’d saved over the years — newspaper clippings detailing fires and explosions at local plants, permit files, emissions registers — evidence of a place under siege.

Over the past several decades, the greater Lake Charles-Mossville area has transformed into a transnational oil and gas hub, with new pipelines, liquified natural gas terminals, and industrial plants rising up out of the swamp and filling the air with the din of construction and the sweet odor of synthetic chemicals. In 2001, the South African chemical company Sasol, whose plant outside of Johannesburg is the biggest single emitter of carbon dioxide in the world, began building an ethane cracker in Mossville to produce ethylene. Sasol didn’t begin the industrial takeover of the town — that had started as far back as the 1940s — but it exacerbated the problems.

After deciding to expand its complex to include an ethylene cracker and a gas-to-liquid plant, Sasol began making offers to buy the properties of Mossville residents, but a study has shown that the company offered significantly less money to Black homeowners, many of whom trace their ancestry back to the founding of Mossville by formerly enslaved people. Some residents decided to take the buyouts anyway, and some decided to stay.

There are four things that the people of Mossville still want, Sullivan Ramirez told me: a lifetime of health insurance, free education, enough money to buy a proper home, and a memorial to honor everyone who’d died with cancer and liver failure.

Once called “the world’s most important chemical,” ethylene is used to manufacture everything from food packaging and airplane engines to polyester and drainage pipes. Toxic as it may be to create, it is an essential ingredient to modern life. But as Mossville learned, some people have to pay a higher price for it. A 2000 study from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry found that the level of dioxins in Mossville residents’ blood was triple the national average.

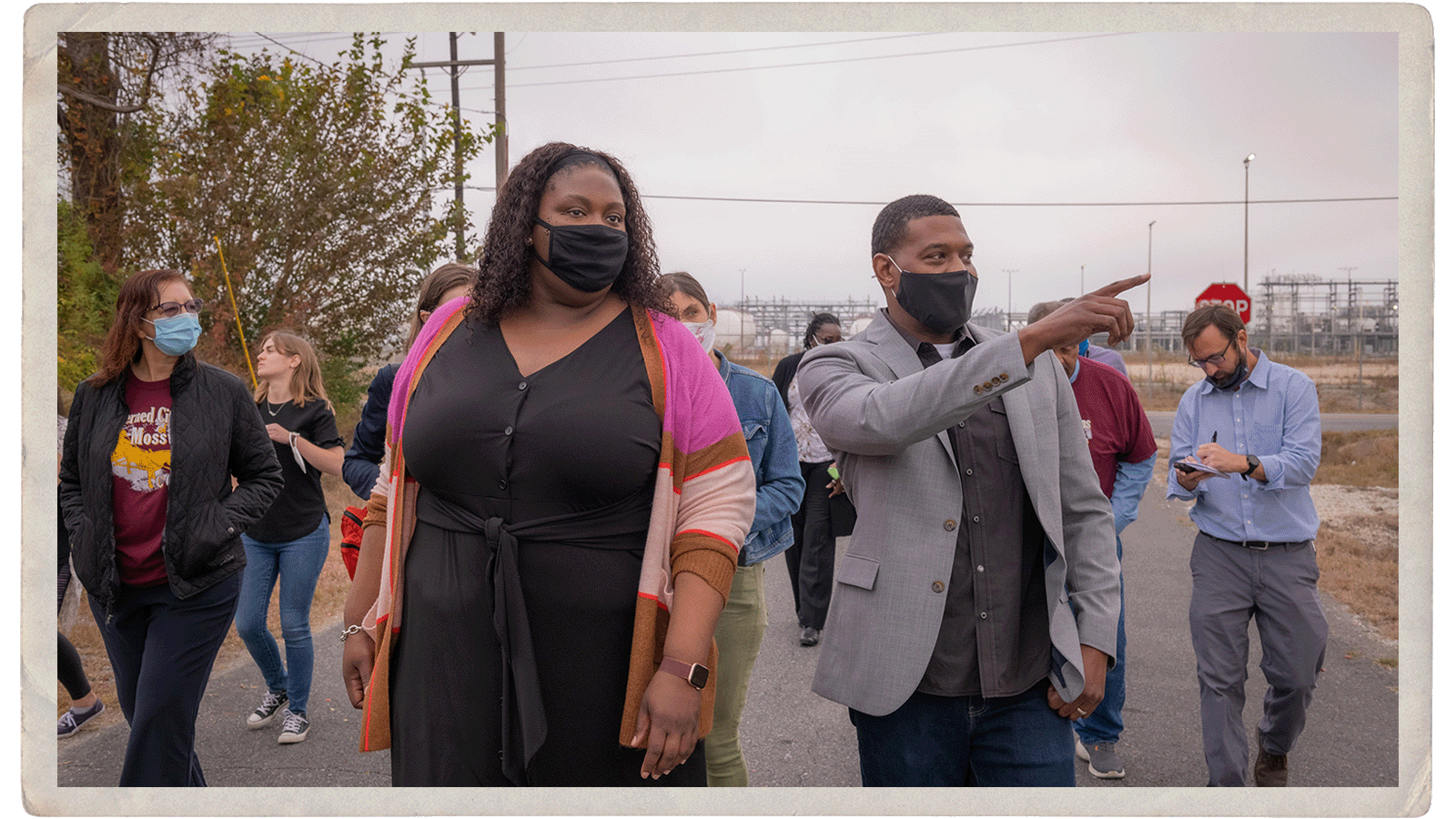

When Regan’s tour bus pulled into Mossville that November, members of the Concerned Citizens of Mossville, a local advocacy group, showed him around. As they drove, one person asked Regan whether he was wearing a face mask to protect himself from COVID or from the air pollution. “Both, in this case,” he replied.

Regan takes a walking tour of Mossville, where the roads leading into town are lined with abandoned homes with faded for-sale signs, in 2021. Eric Vance / EPA

Regan takes a walking tour of Mossville, where the roads leading into town are lined with abandoned homes with faded for-sale signs, in 2021. Eric Vance / EPA“It’s astonishing to see the level — the presence — of industry surrounding this community,” Regan told reporters later that day.

When I returned to Sullivan Ramirez’s house this fall, she was dismayed by the EPA’s actions since Regan’s visit. In January 2022, Regan announced funding for increased air and water monitoring in Mossville, but little else. Companies were rarely fined, or paid minimal amounts, for breaching federal emissions standards, and most importantly, people felt as though there was no way out. (Sasol, which earned $275 billion in 2024, reached a $1.4 million settlement with EPA last April for a string of violations, including a chemical fire at the facility). “EPA is just trying to pacify us. They’ve done nothing but ignore the community folk and what they want,” Sullivan Ramirez said. “We want true change.”

Today, the roads leading into Mossville are lined with abandoned homes with faded for-sale signs. As I approached, the air became acrid and I felt a familiar pressure in my nose, a sign of my proximity to petrochemical pollution. In the parking lot of the old community rec center, a man on a four-wheeler approached and asked what I was doing there. When I said I was a reporter, he waved me off and began driving away.

“Are you from Mossville?” I quickly asked.

He said he didn’t want to talk, that people like me came through from time to time and took pictures of the plants looming over people’s homes — and then they left.

But, he said, he’d been living there all his life. His mother’s home was down the road. The rec center was still open, he said, and if I stayed long enough I might see some kids playing ball. Sure, many folks had left. But for some, he made clear, Mossville was still home.

Mossville seemed to represent more clearly than anywhere I’d visited the terminus of unchecked industrial growth, the final result of a regulatory system administered by industry-friendly state governments and overseen by a federal agency with little power to do anything to upset business as usual. A well meaning EPA, like Biden and Regan’s, could offer an ear to communities in the crossfire or require companies to use better technology and hang up air monitors. But in a place like Mossville, the root of the injustice — a massive chemical complex — is left unchecked.

A playground sits in the shadow of a petrochemical facility in Mossville, Louisiana. More clearly than anywhere I’d visited, Mossville seemed to represent the terminus of unchecked industrial growth. Lylla Younes / Grist

Heading west from Mossville, the problem of pollution hotspots remains starkly apparent on the Texas Gulf Coast, where 10-lane highways fill the air with smog and dozens of industrial companies operate close together and share pipelines, storage infrastructure, and export docks. Regan traveled these highways on his way to Houston’s Fifth Ward, the last stop on the Journey to Justice.

The neighborhood is framed by plants that make concrete along Interstate 45 to the west and metal recyclers dotting Interstate 69 to the east. A cancer cluster, defined as a greater-than-expected number of cancer cases in a particular area, was identified in the community, the result of soil poisoning from Union Pacific Railroad’s former operations. A 2020 Houston Health Department study of the Fifth Ward found that more than 40 percent of the households surveyed had at least one cancer case.

Regan visited two churches and an elementary school in the Fifth Ward. He sat in the front yard of local activist Sandra Edwards’ home, and listened as she detailed the experience of living on contaminated earth. She wanted more than just a reduction in pollution levels. Like Sullivan Ramirez in Lake Charles, Edwards demanded restitution for the harm already done to residents’ health.

“We shouldn’t have to go all the way to the medical center across town,” she told him. “We should bring a facility to this neighborhood for people.”

To get to Houston, the last stop on his 2021 Journey to Justice, Regan traveled down 10-lane highways that fill the air with smog. “We have access to EPA now,” one advocate said, “but what has that actually translated to?”

To get to Houston, the last stop on his 2021 Journey to Justice, Regan traveled down 10-lane highways that fill the air with smog. “We have access to EPA now,” one advocate said, “but what has that actually translated to?”Eric Vance / EPA

Regan promised Fifth Ward residents what he had other communities on the tour — air monitoring, stronger enforcement, and better oversight of the state regulator.

“EPA is exploring ways that we can legally read the Clean Air Act in a way that allows us to take into consideration some of these external factors,” he said. “Do we believe that there’s some vulnerabilities there if people want to challenge us in court? Possibly. But the only way to find out is to test it.”

Longtime Houston resident Leticia Gutierrez left her corporate job for a position at Air Alliance Houston, an environmental justice advocacy organization, after her son was diagnosed with childhood asthma. Administrator Regan’s visit was meaningful, she said, particularly for the residents he met with, who have long family histories of cancer.

At the start of Regan’s term, Air Alliance Houston had really believed that change would come, but, Gutierrez said, “Here we are, four years later, with not much to really speak of.” The industrial facilities surrounding Houston kept up their steady work: In 2023, the city’s smog levels violated health-based standards on 55 days, more than any other year since 2011.

“We have access to EPA now,” she continued, “but what has that actually translated to?”

One thing that the EPA did do, in November, was to release its Interim Framework for Advancing Consideration of Cumulative Impacts, which the agency opened for community feedback. Once the document is finalized, it will provide guidance for local governments to better understand and mitigate the effects of cumulative pollution. That framework, however, will amount to little more than words of advice to state agencies unless a successive EPA administrator moves it forward.

On the last day of my trip, I drove back east to a city that Regan skipped over — Port Arthur, Texas, which is 75 percent non-white and is one of the country’s most important fossil fuel export hubs, where thousands of cubic feet of fracked gas are loaded onto tankers and shipped to Europe each year.

I was on my way to meet with John Beard, an environmental advocate and former chemical industry worker who’s now known for giving his own kind of tours. We were joined by a group of European climate activists traveling between hotspots of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S.

We piled into Beard’s car and drove through the old downtown toward the industrial infrastructure along the coast. Abandoned buildings lined the streets around the city hall. In the surrounding neighborhoods, many homes had boards or plastic sheets instead of windows — damage from past hurricane seasons. Beard began listing facts about the city’s petrochemical history.

John Beard, an environmental advocate and former chemical industry worker, is now known for giving what he calls “toxic tours” of Port Arthur, Texas. Lylla Younes / Grist

John Beard, an environmental advocate and former chemical industry worker, is now known for giving what he calls “toxic tours” of Port Arthur, Texas. Lylla Younes / GristThe first refineries in Port Arthur were built in 1903, he said, and the only time they ever stopped operating was during Hurricane Harvey in 2017. The two largest refineries in the country were located there, within 15 miles of each other. Beard worked as an operator at the one owned by Exxon Mobil for 38 years.

As we crested a bridge overlooking the patchwork of industrial complexes in western Port Arthur, he rolled down the windows.

“You’re smelling wood particles that are laced with formaldehyde,” he informed us, gesturing toward a wood pellet manufacturing facility just out of view.

For several hours, we drove between the different industrial operations in town, stopping to photograph hundred-foot flares and smokestacks emitting billowing steam. Across the river from Sempra Energy’s new liquified natural gas terminal, a group of fishermen were reeling in their daily catch while a pelican perched on a railing nearby, eying them cautiously. According to data from the Texas Cancer Registry, cancer rates among Black residents in Jefferson County, which encompasses Port Arthur and the industrial city of Beaumont to the north, are around 15 percent higher than the state average.

The cruel irony of all the Gulf Coast’s industrial corridors — that mere miles away from neighborhoods where people are too financially stressed to repair their hurricane-damaged homes, the world’s highest revenue-generating companies operate — seemed particularly pronounced in Port Arthur. Workers come from “lily white” suburbs, Beard explained, while locals struggle to make ends meet. The city’s poverty rate hovers around 30 percent, nearly triple the national average.

It’s the same formula I had seen again and again, in the towns Regan visited and in the dozens of others he hadn’t. It’s a problem bigger than the Southern U.S., one that spans Midwestern cities like Gary, Indiana, and southwestern villages like Murray Acres, New Mexico; places where people’s health and futures had been sacrificed for industries that promised to make the country more prosperous and comfortable to all.

It’s also a problem bigger than the EPA. With approvals from elected officials, industrial companies will always set up shop where it’s most profitable for them to: alongside deepwater ports, near natural resource deposits, and in areas where infrastructure like pipelines and roads already exist. The EPA’s job, then, is to somehow regulate the ever-expanding anatomy of industrial America. Its mandate does not require it to consider the necessity or risks of an operation before it comes into being; only to ensure that operation remains in compliance with federal standards. Regan’s EPA tightened many of these rules, requiring for the first time, for example, that synthetic chemical manufacturers monitor the air near their plants. But in a place like Port Arthur, where different kinds of pollution sources operate in the same industrial sprawl, clotting the air and coloring the water, no amount of overhauled regulations (which take years to come into effect) can make it safe. Perhaps this is the most we can expect of the EPA, regardless of whom the president is: incremental progress in the form of pollution-source rule updates, too slow to match the churn of economic growth.

I reached out to Administrator Regan to get his thoughts on what I’d heard as I retraced the path he took four years prior. I also requested an interview with Earthea Nance, the administrator of EPA Region 6, which includes Texas and Louisiana. Neither would meet with me, their press secretaries informed me. They were busy wrapping up their terms and preparing for the holidays, the national office’s spokesperson said, but I could look out for a documentary about the tour soon to be published on the agency’s website. It would answer most of my questions, he assured me.

The video, however, told a familiar story in American politics. Regan decried the environmental pollution he witnessed as “unacceptable anywhere in the United States of America.” And then he championed government funding as the solution. “At EPA, we have designed billions of dollars in grant programs, billions of dollars being invested into our infrastructure to ensure that every single person — no matter the money in your pockets, the color of your skin, or the ZIP code you live in — will have access to clean water, clean air, and safe and healthy lands.” Ultimately, the video betrayed no concern about the threat to such funding under Donald Trump’s next term; nor did Regan himself speak directly to the root of the pollution — industrial activity. “The journey to justice continues,” Regan concluded.

Our final stop on Beard’s tour was a refinery owned by Motiva, a U.S. subsidiary of a Saudi company, separated from a single house by a levee, a weak creek, and a road — maybe 100 feet. Beard knew the woman who lived there, and wondered if she was home. All along the levee, signs warned passersby of the highly pressurized natural gas pipeline that ran under their feet. Long white cushions had been laid across the ditch; Beard asked us to guess what they were. Nobody offered any.

Oil absorbers, he said finally, laid down to absorb the crude oil that floated into the creek.

“What are we making this sacrifice for?” Beard asked. “It is certainly not doing us any good.”

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline Lead in the water and chloroprene in the air: Who does the EPA protect? on Jan 16, 2025.