When God Goes Silent

When you walk through Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, you’re emotionally exhausted by the end. The pain. The suffering. The horror of 6 million Jews murdered, less than a century ago. Children. Grandmothers. Young. Old. Pregnant. Barren. Gassed and cremated with modern efficiency. In Yad Vashem, you see their faces. You learn their stories. The names. The memories. It breaks your heart.

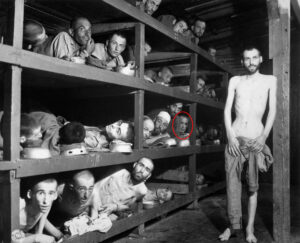

Shortly before you leave, you see a large photo from the Buchenwald concentration camp. Dated April 16, 1945, it shows inmates sleeping three to a bed, with bunks stacked four high. The bodies are nothing more than skin stretched over skeletons.

Tucked away in the second row of bunks in the picture, seventh from the left, is a 16-year-old face. I didn’t recognize it in the picture. But the face would become famous around the world. It’s the face of Elie Wiesel, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986. His book Night recounts his experience of the Shoah, or catastrophe.

Night is the story of Wiesel’s experience at Auschwitz and why he never slept soundly again. When he arrived in Auschwitz, he saw babies tossed in a flaming ditch. How was this possible? How could the world be silent when men, women, and children perished in fires? Wiesel heard his father cry for help as SS guards beat him to death. Wiesel didn’t move to help him, and he never forgave himself.

He was silent.

Wiesel wrote:

Never shall I forget that night, the first night in camp, which has turned my life into one long night, seven times cursed and seven times sealed.

Never shall I forget that smoke.

Never shall I forget the little faces of the children, whose bodies I saw turned into wreaths of smoke beneath a silent blue sky.

Never shall I forget those flames which consumed my faith forever. . . .

Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust.

Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself.

Never.

When three Jewish inmates, including a young boy, were hanged at Buchenwald, Wiesel heard a man behind him ask, “Where is merciful God, where is He?”

Silence. The details they witnessed are too gruesome for me to share. The man asked again, “For God’s sake, where is God?” A voice answered to Wiesel: “Where He is? This is where—hanging here from this gallows.” It was the voice of Wiesel’s own conscience. Wiesel became the accuser. God the accused.

Wiesel survived the camps. And so did his belief in God’s existence. But his doubt lingered. He could no longer trust God’s justice.

How do we account for God’s silence amid the greatest of human suffering? Is God is dead? Did we kill him? Or did we just put him on trial and find him guilty of crimes against humanity?

Elie Wiesel pictured among slave laborers in the Buchenwald concentration camp. Image source: Wikimedia Commons; edited by J. EhleMoral Revolution

The Holocaust precipitated nothing less than a moral revolution in Western civilization. Historian Alec Ryrie observes that World War II exposed Christianity as setting the wrong priorities: “It now seemed plain that cruelty, discrimination and murder were evil in a way that fornication, blasphemy and impiety were not.”

Wiesel survived the camps. And so did his belief in God’s existence. But his doubt lingered. He could no longer trust God’s justice.

In other words, the Holocaust transformed our standards for evil. Before the war, Jesus Christ was the most potent moral figure in Western culture, according to Ryrie. Even non-Christians measured themselves according to his standards of love. But the overwhelming tragedy of the war displaced Jesus as the fixed reference point for good and evil.

Who replaced Jesus as the new moral standard?

Adolf Hitler.

“It is as monstrous to praise him as it would once have been to disparage Jesus,” Ryrie writes in his book Unbelievers: An Emotional History of Doubt. “While Christian imagery, crosses and crucifixes have lost much of their potency in our culture, there is no visceral image which now packs as visceral an emotional punch as a swastika.”

If Christians marched down your street behind a cross, you might shrug them off as eccentrics. But if Nazis marched down your street behind a swastika, you would physically feel their presence as an existential threat to yourself, your family, and the entire public order.

You might not be proud of everything you’ve said and done. You don’t pretend to be perfect.

But at least you know this: You wouldn’t put up with Hitler. You wouldn’t be silent in your protest.

Horseshoe Theory

Wiesel wrote the most harrowing account of the Holocaust I’d read—until I came across Vasily Grossman’s epic novel Life and Fate. A Jewish journalist in the Soviet Union during World War II, Grossman became one of the first writers to observe a Nazi death camp when Treblinka was liberated in eastern Poland.

I was overcome with emotion in one of the novel’s scenes where a young child is separated from his parents during the selection for the Treblinka gas chambers. I can hardly write about the story without weeping. A Jewish doctor could have avoided immediate death due to her profession. Instead, she elected to hold the panicked child’s hands through the horrifying process, all the way until death. The childless woman had one final thought before she perished: I’ve become a mother.

Life and Fate depicts the evils of Naziism like no other work. I’ve never seen such a vivid description of the banality of evil in building and operating a gas chamber. But Grossman doesn’t depict the Soviets as paragons of virtue just because they aren’t Nazis. Despite Grossman’s acclaim as a writer and battlefield witness, Life and Fate almost didn’t survive the Soviet censors. Grossman refused to valorize Stalin for fighting against Hitler. The Soviets wanted to shut Grossman up, just as they had tried to silence God through state-mandated atheism.

Grossman, however, retained an objective standard of evil that allowed him to judge both sides. He helped the world to see that communism and fascism weren’t so much two ends of a left-right spectrum as mirror images of totalitarian evil. They might have been mortal enemies in ideology and war. But in morality, they were partners in crime. They shared a common goal of silencing God’s voice of judgment against their plans for world subjugation.

The war displaced Jesus as the fixed reference point for good and evil. Who replaced Jesus as the new moral standard? Adolf Hitler.

Grossman died in 1964, nearly a decade before Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn published his Gulag Archipelago about the evils of the Soviet state. Solzhenitsyn’s shocking account of Soviet prison camps explains why “don’t be a Nazi” morality hasn’t stopped evil. Anti-Nazi morality fails because it shifts evil from something inside us to something out there among our enemies. It leads us to sanctify ourselves and demonize our enemies, moving us from defendant to judge, as if we’ve become righteous merely by virtue of being born after Hitler’s death. Solzhenitsyn, as a Christian, saw evil not just as something “out there” but also “in here.” He famously observed, “The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart.”

Solzhenitsyn wouldn’t be fooled by Vladimir Putin’s pretensions as defender of the Christian faith in our day. Putin justified his invasion of Ukraine—home of Grossman and of his mother, who died when the Nazis massacred the Jews of Berdychiv in 1941—as “de-Nazification.” When we externalize evil to an out-group, we deceive ourselves in self-righteousness. The rockets Putin has sent raining down on apartment complexes throughout Ukraine should remind us: all manner of evil begins when we underestimate the human penchant for self-deception.

God in the Dock

Another Russian writer anticipated the results when humans make God the defendant, when we sanctify ourselves and demonize our enemies. Fyodor Dostoevsky warned that when we judge God, we don’t replace him with a superior morality. Instead, anything goes. We make the rules. But no one’s in charge.

In Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, Ivan Karamazov argues with his younger brother, Alyosha, about God. Like Wiesel, Ivan is horrified by the suffering of innocent children. Like Wiesel, Ivan protests against God for allowing injustice. Here’s the riveting passage:

And if the suffering of children goes to make up the sum of suffering needed to buy truth, then I assert beforehand that the whole of truth is not worth such a price. . . . Imagine that you yourself are building the edifice of human destiny with the object of making people happy in the finale, of giving them peace and rest at last, but for that you must inevitably and unavoidably torture just one tiny creature, that same child who was beating her chest with her little fist, and raise your edifice on the foundation of her unrequited tears—would you agree to be the architect of such conditions?

Dostoevsky calls this chapter “Rebellion.” No wonder. Ivan says, “It’s not that I don’t accept God, Alyosha, I just most respectfully return him the ticket.” That’s the famous line. Never has a more powerful argument against God been mustered than this: “I believe in him. I just hate him.”

In the next chapter, with Ivan’s poem “The Grand Inquisitor,” Dostoevsky puts Jesus on the literal witness stand, but the trial ends in an unexpected way.

When the Inquisitor fell silent, he waited some time for his prisoner to reply. His silence weighed on him. He had seen how the captive listened to him all the while intently and calmly, looking him straight in the eye, and apparently not wishing to contradict anything. The old man would have liked him to say something, even something bitter, terrible. But suddenly he approaches the old man in silence and gently kisses him on his bloodless, ninety-year-old lips. That is the whole answer. The old man shudders.

Silence, and a kiss.

Is that the best Jesus can do? A kiss?

Why won’t God speak up and defend himself?

He does—in the shouts for justice from the very voices that fault him.

Suffering Servant

Back before the dawn of creation, there was only silence. Then God spoke in the darkness and there was light (Gen. 1:1–3). And when God finished with night and day, when he finished with the eagles and dolphins and gazelles, he created his greatest masterpiece. On the sixth day of creation, God made man and woman. God created nothing else in his image (Gen. 1:26). Nothing else in his likeness. Only man and woman. What does this mean?

It means the dolphins don’t cry out for God in the silence. It means the eagles don’t ask, “Where is God?” It means the gazelles don’t wonder if they should forgive. Every man, woman, and child—regardless of whether he or she believes in Jesus or acknowledges him as Creator—has been made in his image.

We demand justice because we’ve been made by a God who is just. We cry out for mercy because we’ve been made by a God who is merciful. We ask “Where is God?” when babies burn in the fire, when children walk alone into the gas chamber. God’s image can be seen in Elie Wiesel, Vasily Grossman, and everyone else who screams into the dark void. We’re the only creatures who argue with God as our Father. Like exasperated teenagers we shout, “It’s not fair!”

We demand justice because we’ve been made by a God who is just.

And we know something’s wrong, because justice doesn’t always prevail. We know this isn’t the world as God made it. But man and woman have rejected God. We, humanity, have gone our own way. We may be made in the image of God, but we deny his parentage. Eve listened to the lies of the Serpent over the promises of her Creator. Adam listened to Eve instead of God (Gen. 3:17). In the aftermath of this catastrophe, evil roared in victory. Now the human story plays in a minor key. Grief hit home almost immediately when Adam and Eve’s righteous son was killed by his jealous brother. There in the Garden, the seeds of the Soviet gulag were planted. The lies of the Serpent presaged the Shoah. Humanity has turned a deaf ear to God and turned in violence on one another.

The book of Job gives us God’s response to the question of innocent suffering. Of course, God’s response isn’t what we expect. For the evil he endures, Job receives no explanation at all. Yet God is anything but silent when he answers from the whirlwind. The Creator will not be judged by his creation:

Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge?

Dress for action like a man;

I will question you, and you make it known to me.

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?

Tell me, if you have understanding. (Job 38:2–4)

But Job isn’t the only response to innocent suffering we see in the Hebrew Bible. Isaiah was one of the greatest Jewish prophets. In Isaiah 53:7–9, he spoke this word from God about a suffering servant:

He was oppressed, and he was afflicted,

yet he opened not his mouth;

like a lamb that is led to the slaughter,

and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent,

so he opened not his mouth.

By oppression and judgment he was taken away;

and as for his generation, who considered

that he was cut off out of the land of the living,

stricken for the transgression of my people?

And they made his grave with the wicked

and with a rich man in his death,

although he had done no violence,

and there was no deceit in his mouth.

He opened not his mouth. Silence. The lamb led to the slaughter.

The Hebrew Bible, then, gives us a complex answer to inexplicable suffering, to the questions posed by Wiesel and Dostoevsky and everyone else who knows this world isn’t as it should be.

First, we can object because we’re created in the image of God who is just.

Second, we have no right to accuse the Creator, whose purposes transcend our comprehension.

Third, an innocent servant’s suffering will somehow pardon the transgression of God’s people.

His chastisement will bring us peace. By his wounds, our world will be healed (Isa. 53:5).

Sounds of Salvation

The first sounds of salvation emanated from a hill outside Jerusalem called Golgotha. For six hours, the Creator and Sustainer of the universe hung on a Roman cross, slowly dying. In solidarity with its Maker, the land descended into darkness of night (Mark 15:33). Then Jesus cried out with a loud voice, “Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?” That is, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34).

Night has never been darker. Quiet has never been quieter.

Jesus cried out again, and he died.

The Son offered friendship to all, but he made enemies of those who claimed to speak for God while they made every follower “twice as much a child of hell” (Matt. 23:15). The Son’s every good deed, his every healing miracle, enraged the self-righteous. In their show trials, they couldn’t find a single transgression by Jesus. Still, the religious and political leaders threatened by his innocence silenced his prophetic voice.

Then, on the third day, the sun rose. Light shone on Jerusalem. The women who loved Jesus went to his tomb. “An angel of the Lord descended from heaven.” The sound was deafening. The earth shook while he rolled the stone away from the tomb. The light was blinding. “His appearance was like lightning, and his clothing white as snow” (Matt. 28:2–3). He came with news of a new creation.

The former things had passed way. “In Christ God was reconciling the world to himself” (2 Cor. 5:19).

“For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin,” we read in 2 Corinthians 5:21, “so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.” Theologians call this the “great exchange.” In union with Christ, he takes on our sin and dies the death we deserved on the cross. He gives us the righteousness of his sinless life so one day we’ll hear from our Father, “Well done, good and faithful servant” (Matt. 25:23).

God Has a Son

For now, the sounds of slaughter still haunt every corner of the earth. “Never again” gives way to war crimes in familiar Ukrainian cities with yet another land war in Europe. The League of Nations couldn’t stop the last major war. The United Nations can’t stop this one. Over the clanging gong of breaking news, we listen for the first notes from a trumpet that will signal the end of evil (Matt. 24:31). Then, final judgment will be rendered to the butchers of Buchenwald and Berdychiv. No evil word will go unpunished. On that day, every child’s cries will find consolation.

For God himself has a Son. Though he did no wrong, that Son suffered. And his suffering availed to our eternal salvation. This sheep may have been silent. But his sacrifice silenced the original accuser, Satan. The first enemy can rage. In the end, however, Satan cannot win.

The first enemy can rage. In the end, however, Satan cannot win.

Even now, God prepares to send his Son again. In Christ, new creation is coming. Jesus overcomes evil with good (see Rom. 12:21). He’s making all things new (Rev. 21:5).

When Christ returns, all who believe will kiss the very lips that were betrayed. Jesus will wipe away every tear from our eyes. Death will be no more!

No mourning. No crying. No pain.

We’ll hear a “great multitude, like the roar of many waters and like the sound of mighty peals of thunder, crying out, “Hallelujah! For the Lord our God the Almighty reigns” (Rev. 19:6).

God is never silent. His sheep hear his voice (John 10:27). Through the noise of this evil age, they hear the most reassuring promise of all: “I give them eternal life, and they will never perish, and no one will snatch them out of my hand” (John 10:28).

He hears your cries. He sees your tears.

Your Father may not owe you an answer. But he gives you his Son.